British poet Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne contributed to the ferment of new ideas about art, religion, poetry and politics in the early twentieth century. She was a suffragist, socialist and freethinker as well as a poet, and her social networks included artists, feminists, reformers and revolutionaries. This is the text of a talk I gave at a Socialist History Group seminar at the Institute for Historical Research, London, on 20 February, 2023. I have added notes and references, plus a new Afternote speculating about possible connections between individuals and groups in Britain and Chicago.

Download: Poet among the Social Reformers as a Word docx file

Poet among the Social Reformers as a PDF

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Key Words: aphorisms, feminism, freethought, poetry, suffrage, suffragette, socialism, social reform, Society of Friends of Russian Freedom.

People: Jane Addams, Maurice Browne, Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne, T.K. Cheyne, Stanton Coit, Peter Kropotkin, Felix Volkhovsky, Sydney Cockerell, Elizabeth Spence Watson, Robert Spence Watson, Ellen Gates Starr.

More information and articles about Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne here.

‘A Poet among the Social Reformers’

Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne: Suffragist, Socialist and Freethinker

In the winter of 1915, thousands of garment workers in Chicago, many of them women and girls, many of them immigrants, went on strike — the latest in their bitter struggle against exploitative wages and conditions. The strikers were met with extreme violence, much of it at the hands of the police.[1] At a mass meeting held to protest against police brutality, a woman speaker read out a sequence of three poems, ‘The Man upon the Cross’, which drew on Christian imagery to speak out against contemporary cruelty and injustice. According to newspaper reports, these ‘startling’ poems ‘caused a sensation’ in the audience.[2] Their author, British poet Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne, never as far as I know visited the USA, but her words resonated beyond national boundaries.

Though she had some recognition in her own time, by the time of her death in 1931 Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne had already been largely forgotten, and few people today have heard of her. Her books are hard to come by, and archival sources scanty; it’s taken me many years to gradually piece together a version of her life. I started before the internet began to transform research, but more recently the increasing digitisation of resources, including access to newspaper archives, has enabled me to get a fuller picture of how her work was received at the time. Looking at her life in its wider context gives insights into the new social movements of the early twentieth century, the overlapping social, political and cultural networks in which they flourished, and the ways in which radicals of all kinds were re-imagining their world in the years leading up to the First World war.

Gibson Cheyne was a prolific writer, and alongside her numerous books her work also appeared in mainstream journals and the little magazines of literary modernism, the radical press and the publications of Theosophists, Freemasons, and Ethical Societies. Besides being read out at protest meetings, her poems were quoted by social investigators and medical reformers, set to music, and used in new alternatives to traditional religious services.[3] By 1911 she was sufficiently well known as a poet to be invited to appear in Who’s Who, where she declared herself to be ‘a suffragist, socialist, and freethinker’. She repeats that same phrase elsewhere, clearly seeing these labels as an important part of her public identity. [4] In this talk I’ll be looking at her connections with suffrage, socialist and freethought circles, and will suggest that like these circles, the identities overlap, and need to be understood in relation to each other.

I’ll begin with a brief sketch of her life, and draw out my themes as I go along. Elizabeth Gibson was born in 1869, the third of eight surviving children (four other siblings died in infancy). The family lived in Hexham, a small market town near Newcastle, and Elizabeth remained in the parental home until marrying and moving to Oxford in her early forties. Her father was a chemist; the family was comfortably off but not wealthy, and all the children were expected to work for their living. Elizabeth was educated at the pioneering Gateshead High School, which offered progressive non-sectarian schooling for girls. After leaving, she took on the responsibility for home-schooling her brother Wilfrid, nine years her junior. In what was by all accounts an unhappy household, she and Wilfrid developed a powerful bond, and under her influence he too became a poet, whose reputation would eventually outstrip hers.

By the mid 1890s, Elizabeth Gibson, as she was then known, was getting her poems published in magazines, and her first book, The Evangel of Joy, came out in 1899. Besides poetry, she also produced several collections of aphorisms and reflections: some of these were little booklets aimed at the Christmas gift market (the sort of thing you might see now by the till in Waterstones).[5] Over the years a number of her aphorisms (or ‘sayings’, as she called them) also appeared in newspapers all over the country under such headings as ‘Thoughts for the Day’— in spaces where it was exceptionally rare to see a woman’s name appear alongside such thinkers as Tolstoy, Emerson, Confucius and Shakespeare.[6] However, making a name for yourself isn’t the same as making a living, so, all the while continuing to publish numerous books, none of which sold particularly well, she pieced together an insecure income by working as a day governess and a typist.[7] At the age of forty, she had a breakdown, and, fearful for her health, her father began to provide her with a small allowance.[8] Soon after, she was able — for the first time — to list her occupation in the 1911 Census as ‘author’.

Her identity as a writer had developed during the 90s heyday of the ‘New Woman’, one of a generation who, long before the end of Queen Victoria’s reign, were rejecting the confines of so-called Victorianism, such as the notion of separate spheres for men and women. Particularly hot topics for debate were the inequitable status of women in relation to marriage, and, not least the double standard of sexual morality.[9]

Many of Elizabeth’s more autobiographical writings, then and later, related to her turbulent emotional life, which included passionate relationships with both men and women. Some of her love poems, described by one reviewer as ‘psychologically erotic’, were frank expressions of female desire.[10] Other, less evidently personal, poems and prose pieces critiqued the sexual status quo. She was in the minority of feminists who went beyond criticism of inequitable marriage laws to challenge the institution itself. She believed that the only moral relationships were those which — married or not — integrated love, passion, responsibility, and mutual respect.

Few situations are more immoral than the generality of marriages.

—Elizabeth Gibson, 1909 [11]

For example: To her, the pervert is the cold husband who to save his reputation stands between his wife and her true lover. To her, the pervert is the woman who marries without love, chooses not to have children, and then denounces her maid for having an ‘illegitimate’ baby. To her, bourgeois respectability and the established church are the enemies of the true virtue, which is love.

Ideas like these were not always welcome amongst the feminist and socialist groups of the time, many of whom were anxious not to have their causes distracted from by allegedly peripheral or secondary concerns, or tainted by allegations of immorality. Freethought circles were more open to debates about such matters, but as I’ll show later, Elizabeth could be a bit of an awkward fit there as well.

It seems she was never much of a joiner, and despite her self-identification as a socialist, to date I haven’t found any evidence that she was involved with a specific socialist group or ism — though that doesn’t mean she wasn’t. She was, however, part of an expansive literary, cultural and political network that included many socialists. A good illustration of this is her connection with the newspaper Free Russia, an English language paper founded in 1890, and produced by exiled Russian socialists and revolutionaries living in Britain. Between 1900 and 1902, Elizabeth worked with its editor, Felix Volkhovsky, to produce English versions of Russian poems for the paper.[12]

Free Russia was backed by the Society of Friends of Russian Freedom (SFRF), an organisation whose broad range of supporters included Liberals, Quakers and nonconformists; Fabians, anarchists and socialists; writers, artists and suffragists. The SFRF’s founders included Liberal Quakers Robert and Elizabeth Spence Watson — a married couple closely involved in founding and supporting Elizabeth Gibson’s old school, Gateshead High. The Spence Watson’s daughter, Mabel, had been one of Elizabeth’s teachers, and some of her pupils, possibly Including Elizabeth, were present at the Spence Watsons’ home on the occasion when an escapee from a Russian prison showed horrified fellow guests his hands and wrists, scarred by manacles.[13] Whether or not Elizabeth was there that evening, she was certainly aware of such stories, and the Society was instrumental in creating a swell of public opinion against the brutalities of Tsarist Russia.

In 1899 another co-founder of the SFRF, the Russian anarchist Peter Kropotkin — then living in England — published his gripping Memoirs of a Revolutionist. It told of his battles against injustice and oppression, his political development from republicanism to anarcho-communism, and his incarceration and subsequent escape from prison. Elizabeth said it was the most interesting book she had ever read, and she shared her borrowed copy around her friends.[14] (A few years later, the book would become an inspiration to some of the militant suffragettes.) Its tales of revolutionary heroism and resistance to oppression included praise for Russian democratic feminists as well as a younger generation of women, ‘who went about as typical nihilists, with short-cropped hair, disdaining crinolines, and betraying their democratic spirit in all their behaviour’, and who risked everything in order to bring about change for the masses.[15] Kropotkin’s thoughts on the value of poetry, and its capacity to arouse sympathy for ‘the down-trodden and ill-treated’ may have particularly appealed to Elizabeth: ‘Read poetry:’ he wrote, ‘it makes men better’.[16]

Such words call to mind William Morris’s arguments for the importance of art for everyone. Elizabeth was familiar with Morris’s writing, discussing it with her friend Sydney Cockerell, who had as a young man been Morris’s private secretary. [17] Though many of Elizabeth’s early poems were influenced by the late C19th aesthetic and decadent movements, with their insistence on Art for Art’s sake, she soon began producing work more in line with Morris’s belief in Art for Life’s Sake. Her writing, as she saw it, was her contribution to making a better world.

The years leading up to the First World War saw what some historians call the Great Unrest, when the British Isles underwent what some hoped — or feared — was a revolutionary upsurge of class war, sex war, and anti-colonial activism. It was in this context that explicitly socialist ideas first became noticeable in Elizabeth’s work, as seen in aphorisms such as these:

People agitate to find work for the unemployed poor, but forget to impose work on the unemployed rich.[18]

Few oppressors realise that the foregone result of oppression is revolution.[19]

The millionaire is responsible for the bomb-throwing of the Anarchist.[20]

The majority of her aphorisms were much less explicitly political, and it was the more anodyne ones about social morality that got chosen for newspaper Thought-for-the-Day-type columns. But there are many that expressing anti-nationalist, anti-racist, anti-imperialist ideas and could have been written today:

True patriotism is a burning shame for our country’s injustice and wrongdoing.[21]

(She was for many years anti-war, as well, though that position would change during the course of World War One.)

A number of her books of aphorisms were produced by the Simple Life Press as part of a series — including works by Tolstoy, Thoreau and Emerson — that aimed, according to the publisher, to promote ‘social justice, religious truth, and the meaning and conduct of life.’ The books were designed to be affordable, being published simultaneously in two editions: one cheap, the other more fancy. Reviewing Elizabeth’s Well by the Way, in 1913, the Daily Herald said it should ‘find a corner in many workers’ libraries, and its philosophy a … place in many workers’ imaginations.’ [22]

She wrote poems with socialist themes too. Some of these used conventional poetic forms, and drew on the familiar imagery of red flags, flying the standard of freedom, throwing off chains and so on. In others, she took a different approach, especially in her use of dramatic monologues that abandon rhyme and poetic language in favour of free verse. One example of this is ‘The Mother’, written in the voice of a wealthy mother talking about the poor mother she employs to clean and sew and care for her children. Here’s an excerpt:

I think that when people are poor it is their own fault. […]

I take all that is given to me and my children;

But I am afraid of pauperizing the poor mother and her children …

One day when I was explaining these things to her

She retorted that it is I who am the pauper;

And that her children […] must go hungry that mine may be pampered […]

So I told her she was talking politics, which are not women’s business,

And that the Socialists had been perverting her. […]

Elsewhere in the poem, she says that she is always polite to the poor mother because: ‘I am afraid/ She might strike me or my children/ And demand her and their share of everything …’ [23]

Given a straightforward political interpretation, the full version of ‘The Mother’ reads as a caustic intervention into the then current heated controversies over the very beginnings of the welfare state (for example the debates over the use of public funds to provide, even on the most limited basis, such things as school meals, medical services for children, pensions, or national insurance). Unlike other dramatic monologues, which tend to be about individual psychology, ‘The Mother’ gives us a political dimension to the personal — and a personal dimension to the political. While some doubted if such a piece should even be called poetry, others admired its Whitmanesque style and its powerful psychological insight. The poem was reprinted in medical journals, and quoted in sociological texts: evidence of its relevance to a variety of social reformers.[24]

It is also one of a number of poems criticising middle and upper-class women for their treatment of women who worked for them; for their concern with own lives and freedoms at the expense of other women — and I’m going to look next at Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne the suffragist.

Image from New York Public Library

The first decade of the new century saw the rise of a new wave of militant suffrage. Both militant and non-militant suffrage groups were active throughout Elizabeth’s home region of north-east England and the Scottish borders, but I have been unable to find out if she belonged to any local groups. She certainly had friends in England and Scotland who did, and she seems to have been in supportive contact with both militant and non-militant organisations — the boundaries between which were not nearly as clearcut as commonly believed. She did, however, join the committee of the national Women Writers Suffrage Group, founded in 1908 ‘to obtain the vote for women … using ‘methods … proper to writers — the use of the pen.’ [25]

Surprisingly, given her own self-description as a suffragist, there is little direct mention of suffrage as such in her writing, but an excerpt from one of her poems — in a book she donated to the Suffragette Library — throws some light on this relative absence:

I met a woman walking through the world […]

[…] I asked her where she was going.

‘Everywhere’ she replied.

I asked her whence she came,

And she answered: ‘From the ends of the earth.’

‘Of what land are you an inhabitant?’

‘Of every land I have heard of.’

‘Of what city are you a citizen?’

‘Of every city I can imagine.’ [26]

For her, as for many others in the Suffrage Movement, the vote was a necessary — but limited — part of a much wider struggle for social and political transformation; imagining a new world was part of that.

Not long after she wrote this poem, her own life was about to change. I took the title of this talk, ‘‘A Poet Among the Social Reformers’ from a front-page article in the Christian Commonwealth, a monthly paper billing itself as ‘the organ of the progressive movement in religion and politics’. The piece praised Elizabeth as ‘an imaginative writer of rare distinction’ and her poetry for its contribution to social activism.[27] The author, Thomas Kelly Cheyne, was on the paper’s editorial board. A few months before this article appeared, he had written to Elizabeth out of the blue, telling her that her books were what he had been waiting for all his life.[28] Less than a year later, they were married. At first glance, they seem an unlikely couple —Thomas was, amongst other things, an Anglican priest — and the alliance of the self-proclaimed freethinker poet with a Church of England clergyman raised a few eyebrows, even causing comment in the gossip column of the Daily Mirror.[29] Thomas was also an eminent and controversial biblical scholar, a retired emeritus Professor at Oxford University. A pioneer of the German criticism — which approached the Bible as series of historical texts, not literal truth — he was once denounced from the pulpit in Oxford for his views on the virgin birth.[30]

By the time he and Elizabeth met, he was a widower, almost 70, living with disability and poor health. ‘His afflictions are great’, she told a friend, ‘but he is the cheerfullest person I have ever known … He is very advanced and progressive in all his ideas’ and ‘like me, [he] believes in the fusion of all religions, not the predominance of Xtianity [sic].’[31] The two were initially drawn together by their shared values, especially their commitment to universal brotherhood, feminism, and an openness to all religions. From their meeting to his death would be only a little over four years, yet the relationship, though brief, appears to have been happy and enabling for both. They seem to have found ways to share and encourage one another’s writing, and many of the more personal poems Elizabeth published during this period speak of her newfound happiness.

Although her time was now mainly divided between writing and caring for her husband as his health deteriorated, she maintained some level of political involvement. In 1912-13 the couple joined in public protests against forcible feeding of imprisoned suffragettes.[32] At Christmas 1914, with the First World War already underway, Elizabeth was one of over 100 feminists who signed an Open Letter to the Women of Germany and Austria, appealing to women to work together for peace.[33]

But a few weeks after the letter was published, Thomas Cheyne died, and Elizabeth left Oxford for London, where for the rest of the war years she led a peripatetic life, continuing to write while doing various kinds of voluntary work — mostly involved with a variety of Christian organisations. How does her increasing involvement with Christianity align with her claim to be a freethinker? Her views had begun to change following her husband’s death, but the question is complicated — not least because the category of freethinker is itself both ambiguous and changeable.

Here are some of her earlier thoughts on religion:

He alone is free who is creedless and without nationality.

God is not the God of one religion, but of the universe.

Jesus came to succour humanity, not to found a religion.[34]

Jesus, she says, is not a Christian, but a socialist and freethinker. To her, freethinking is not rejecting religion as such, but reconceiving it outside institutional constraints. Art for Life’s Sake — and Religion for Life’s sake.

Her writings on the topic are numerous, but brief and provocative rather than analytic. To pick out the most consistent ideas: she believes in some kind of God — but says that God is created by humans, can be male or female, and is present throughout nature. Truth can be found in all religions, but Churches, creeds and dogmas are the enemies of true religion.

After the war ended, she enrolled to study Theology on one of the courses for women recently set up by Kings College London. This suggests she was heading in a new direction, but within a few months she had a mental breakdown and spent the last years of her life in an asylum, so it’s hard to predict how her ideas would have developed.

Her readers tried, but found it hard, to label her beliefs: some thought of her as her a pantheist; her husband called her a panentheist (someone who believes that God/ the universal spirit is manifest throughout the universe but also transcends it). Humanists thought she was a theist — but nevertheless commended her work for its relevance to humanism.[35] Some of her poems were read from pulpits to Christian congregations. And of course, as I mentioned at the beginning of this talk, they were employed in political contexts as well.

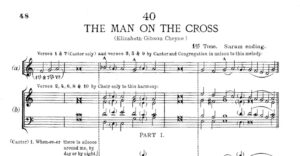

A couple of ‘The Man on the Cross‘ poems read out at the Garment Workers Strike meeting had earlier been set to music in a volume called Social Worship, intended for use in those Ethical Churches where traditional Christian worship was replaced with a variety of what would now be called humanist ceremonies.[36] What all this suggests is that her work could be selected from and interpreted in different ways, that it could inspire a broad range of people who all sought, in their own way, to change the world they were living in.

Poet, suffragist, socialist, freethinker: it wasn’t just her own identities that overlapped and intertwined, feeding into one another, so too did the social movements in which she participated. Reading Elizabeth’s’ poems about the poor Mother who wanted her share of everything, about the woman of the future who says ‘I am going everywhere, a citizen of every city I can imagine.’ I’m reminded of a local May Day Rally I went to in the mid 1970’s with friends from my Women’s Liberation group. One brought along her own home-made placard that said ‘We Want Everything’, and we marched alongside a trade union banner with the slogan ‘Unity is Strength’. We were then just beginning to find out about earlier generations of women activists in Britain and the USA who, like those striking garment workers, wanted ‘Bread — and Roses too’. Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne’s’ poetry and prose can be seen as her contribution to the creation of a shared culture – from which new kinds of society could be imagined.

Afternote: Chicago Connection/s

As I was putting together the detailed references for this talk, preparatory to publishing it online, I was struck by how often Chicago turned up as the place of publication. This could be coincidence, or an artefact based on which archives have survived, and which magazines and newspapers have been digitised. But maybe there was more to it. Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne was not well known in the USA; none of her books were published there, and there is no evidence that she ever visited. Yet, as illustrated by my opening example of the public meeting in support of the Chicago garment workers, some of her poems and other writings had an ongoing impact in a range of progressive political and literary contexts — at least in Chicago.

So how did her work become known there? I knew there were people and groups in Chicago with similar political and artistic interests to hers, and that her work later appeared in a couple of the little literary modernist journals published in the city. What follows are some preliminary notes on the various linkages I began to trace out, taking the strike solidarity meeting as a starting point. I’m making them available here in the hope that other researchers in may find the information useful in developing their own pictures of the complex and shifting connections between people, places and organisations.

Chicago and Hull House

The person who read out Elizabeth’s poems at the 1915 strike meeting was Ellen Gates Starr. Starr and her partner Jane Addams were American Christian socialists and feminists who, inspired by a visit to London’s Toynbee Hall settlement, became co-founders in 1899 of Hull House, a secular settlement, run by women, that provided a range of social services and educational activities for working class people in a largely immigrant district of Chicago. Both Starr and Addams were active campaigners for social justice, and included a wide range of radicals and progressives among their friends. Kropotkin was one of many international visitors to Hull House, staying there for a week in 1901, and Addams, though a pacifist, sympathised with the advocates of resistance and revolution in Russia.[37] She also had transatlantic connections with the British women’s suffrage movement; a photograph in the Library of Congress shows her with fellow suffragists Emmeline Pethick Lawrence, a leading figure in the British movement, and Alice Thacher Post, managing editor of the progressive Chicago journal The Public — which in 1912 published Elizabeth’s poem ‘the Mother’.

The University of Chicago

The mass meeting was held in the Kent Theatre at the University of Chicago Campus. A possible connection here is Charles Richmond Henderson, social reformer and Professor of Sociology at the university. He had previously used some of Elizabeth’s poems to illustrate arguments in his own work, and he quoted one of the ‘Man on the Cross’ poems while on a lecture tour of India China and Japan. (Henderson describes Elizabeth in his books not as a poet, but as the wife of well-known Biblical scholar Thomas Kelley Cheyne; leaving aside the evident sexism of that, it might indicate that Thomas played a part in publicising her work via his own network of progressive religious academics).[38]

‘The Man on the Cross’ poems.

‘The Man on the Cross’ was, confusingly, used variously as the title for one, two, or three poems from a sequence that, as far as I know, first appeared under the titles ‘The Cry’, ‘The Cross’, and ‘The Excuse’, in Elizabeth’s self-published 1911 collection, The Way of the Lord, (A related poem, ‘The Woman upon the Cross’, was published a few years later). Some copies of this book definitely made their way to the USA — for instance it is reviewed in 1912 in the Christian Register, a Unitarian paper published in Chicago and Boston, and my own copy carries the stamp of a Bible School in Oklahoma.

Stanton Coit’s 1913 Social Worship, mentioned earlier, is another possible source. Coit, an American living in England, retained his connections in US progressive circles, and though published in London, Social Worship was known and used by ethical groups and progressive Christians in his home country. As far as I can determine, this is where the poems were first retitled as ‘The Man on the Cross’, a detail which suggests that the book may have been used as a source for the two poems subsequently reprinted — using that title, and in similar contexts — in the USA. until at least the early 1940’s.[39] However, the poems may also have been circulating in other ways, as discussed below.

Maurice Browne, the Samurai Press, and the Little Theatre.

At least one person in Chicago at the time actually knew Elizabeth in person. Maurice Browne, originally from England, had an extensive range of overlapping political and cultural connections in both countries. Before emigrating to the USA, he had been a co-founder of the Samurai Press, which between 1907 and 1908 published several books by both Elizabeth and her brother, Wilfrid Gibson. In 1912, Browne moved to Chicago, where, with his wife Ellen van Volkenberg Browne, he co-founded the influential Little Theatre — inspired in its turn by the theatre group started by Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr at Hull House. In 1916, Browne produced Wilfrid Gibson’s feminist-inspired play Womankind at the Little Theatre.[40]

Another person involved in the Little Theatre’s early days was Jane Heap. who in 1916 joined her then lover, Margaret Anderson, in producing the Little Review, which that year published the Man on the Cross poems under their original titles. An editor’s note, which situates the poems very explicitly at the intersection between literary modernism political activism, refers to the readings at the strike meeting and then comments, ‘I do not know whether these poems have been published elsewhere or not.’ This remark implies that they were being shared around individuals and groups in some more unofficial form, perhaps orally, or in transcript.[41]

Harriet Monroe, Poetry magazine, and Wilfrid Gibson

Harriet Monroe’s Poetry was the other Chicago based modernist little magazine to publish poems by Elizabeth: the first, ‘Partings’ appearing in July 1913, followed by ‘A Poet to His Poems’ in September 1915. These poems (both non-political in content) also appeared in Elizabeth’s self-published 1913 collection In the Beloved City He Gave Me Rest; they may have been taken from there, or she may have submitted them directly to the magazine — the records are inconclusive, though she was in touch with Monroe at some point around this time, and was paid for the work.

By 1915, her brother’s poems had become much better known than her own. In August 1915, Poetry included six of the war poems from his ground-breaking collection Battle, and the following year Macmillan republished the book in the USA. By the end of 1916, Wilfrid was planning a reading and lecture tour of the USA; letters between Jane Addams and Harriet Monroe show them looking forward to his visit, and discussing the possibility of him lecturing at Hull House. In the event, Wilfrid based himself in Chicago for three months of his six-month stay, becoming good friends with Harriet, and keeping in touch with her after his return home. [42] His letters to Harriet never mention Elizabeth, and it seems unlikely that he used his time in the USA to promote her work as well as his own. Elizabeth, on the other hand, took every opportunity to promote him.

* * *

However Elizabeth’s work arrived in Chicago, asking the question has shown again that ‘socialist, suffragist, and freethinker’ can best be seen not as personal attributes or fixed political categories, but as indications of relationships — created through actions and stitched together by friendships and shared beliefs — within and between the ever-shifting and changing social movements of her time.

- See, e.g. ‘The Garment Workers Strike’, November 1915, International Socialist Review, 1915, Vol. XVI No 5, Chicago, pp. 260-264. ↑

- According to an editor’s note accompanying the three poems in the Little Review, April 1916, Vol III No 2, Chicago, p.13: ‘[T]hese poems … were read by Ellen Gates Starr in a mass meeting in Kent Theatre on the University of Chicago campus—a mass meeting in protest against police brutality during the garment strike.’ For more information on Ellen Gates Starr, and Chicago connections, see the Afterword to this paper. For the impact of the poems, see Dorothy Willis ‘News Notes and Comments on Events Concerning Women’, June 2 1916, and June 24, 1916, Los Angeles Evening Express. ↑

- See Judy Greenway, 2014, Wilfrid and Elizabeth Gibson, Art for Life’s Sake: Politics, Religion and Poetry, parts of which I have drawn on for this talk. First published in Dymock Poets and Friends, 13:2014, pp.36-38. More articles and information about various aspects of Elizabeth Gibson’s life and work. ↑

- Who’s Who, 1912; and see Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne, nd [probably c1912/13] unpublished ms autobiographical note in the archives of Poetry: A Magazine of Verse. Records, (Box 4, Folder 18), Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Centre, University of Chicago Library. ↑

- Examples include her first book, The Evangel of Joy, 1899, Grant Richards: London — a slim volume of aphorisms intended for the Christmas market, as was Flowers from Upland and Valley: A Daily Calendar, 1905, A. C. Fifield, Simple Life Press: London, which had ‘Greetings from ____’ handily printed on the flyleaf. (See Julia Dawson’s review in the Clarion, 15 December 1905.) ↑

- The vanishingly few women whose aphorisms very occasionally appeared alongside hers include Elizabeth Barrett Browning, George Eliot, and E. Nesbit. ↑

- See 1901 census, the autobiographical note mentioned in note 2, and her letters to Sydney Cockerell in the Cockerell papers, British Library. ↑

- Elizabeth Gibson to Sydney Cockerell, 30 August 1910, Cockerell papers, British Library. ↑

- Lucy Bland, 1995, Banishing the Beast: English Feminism and Sexual Morality 1885-1914, Penguin: Harmondsworth. ↑

- Westminster Gazette, 18 January 1908 (as labelled on cutting in the Elkin Mathews Archive, item 7:5:415, Special Collections, University of Reading.) ↑

- Elizabeth Gibson, 1909, Welling of Waters, E. Gibson, Hexham, p.18. ↑

- Elizabeth Gibson letter to Felix Volkhovsky, 3 June 1900. Vera Volkhovsky Papers (66M-197) Houghton Library, Harvard University. Thanks to Carol Peaker for this reference, and for alerting me to Gibson’s connection with Free Russia and Volkhovsky. See also Elizabeth Gibson letter to Sydney Cockerell, 14 June 1900, Cockerell papers, British Library. Though Elizabeth had previous experience of translating from Italian, it is unlikely that she knew Russian, and it seems that Volhovsky made prose translations of the originals, which she then rendered into verse. Carol Peaker’s 2006 PhD thesis, Reading Revolution : Russian Emigres and the Reception of Russian Literature in England, c1890-1905 gives valuable insights into the circles around Free Russia. ↑

- Olive Carter, nd [c1955)], History of Gateshead High School and Central Newcastle High School, Girls’ Public Day School Trust, Newcastle. p 16. The Spence Watson family remained involved with the school during Elizabeth’s time there. Robert Spence Watson was the President of the Newcastle Literary and Philosophical Society, and is likely to have known Elizabeth’s father, also a member, through that. Visitors to the Spence Watson home at Benham Grove included Kropotkin, Stepniak, Volkhovsky, Willam Morris, and other reformers and revolutionaries from around the world. ↑

- Elizabeth Gibson letter to Sydney Cockerell, 4 June 1900, Cockerell papers, British Library. ↑

- Peter Kropotkin, 1899, Memoirs of a Revolutionist, Houghton Mifflin, New York and Boston. p.262. ↑

- ibid p.95. ↑

- Although Morris, too, had been involved in the early days of the SFRF, he died in 1896, and it’s unlikely Elizabeth ever met him in person. Cockerell, who became Morris’s executor, had a wide range of political and literary friendships. It was he who lent Elizabeth Kropotkin’s Memoirs. ↑

- Elizabeth Gibson, 1909, Welling of Waters, E. Gibson, Hexham. p.17. ↑

- Ibid p.26. ↑

- Elizabeth Gibson, 1910, Blossoms of Peace, E. Gibson, Hexham. p.9. ↑

- Elizabeth Gibson, 1908, Sparks from the Anvil, E. Gibson, Hexham. p.27. ↑

- Review of Elizabeth Gibson’s Well by the Way in Daily Herald, November 19, 1913, p.2. ↑

- ‘The Mother’ Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne, nd [1911], The Way of the Lord, Mrs. Cheyne, Oxford. pp.32-3. The full version is available in this selection.↑

- See, for example, Medical World, August 1912, [USA]. p.347, where it is renamed ‘The Two Mothers’; Charles Richmond Henderson, 1914, The Cause and Cure of Crime, A.C. McClurg & Co. Chicago. p.39; The Public, January – December 1912, Vol. XV. Chicago. p.239, amongst others. ↑

- Sowon S. Park, 1997, ‘The First Professional: The Women Writers’ Suffrage League’, Modern Language Quarterly, 1 June 1997; 58 (2): pp.185–200. [see 189 fn1] doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/00267929-58-2-185 ↑

- Elizabeth Gibson, 1910, ‘Woman’, From the Wilderness, E. Gibson, Hexham. pp. 35-36. See inscribed copy in Museum of London Suffragette Fellowship Collection, accession number 50.82/248 The full version of the poem can be read here, together with a few others relating to the theme of this paper. ↑

- T. K. Cheyne, 1911, ‘A Poet Among the Social Reformers’, Christian Commonwealth, Jan 25 1911, Vol. XXXI, No.1528. p297, [Front page]. ↑

- Elizabeth Gibson letter to Sydney Cockerell, 6 May, 1911, Cockerell Papers, British Library. ↑

- Daily Mirror, Jan 23 1914, p.5. ↑

- Oxford Chronicle, 24 June 1904, p11. His denouncer on this occasion was the Rev. R.W. Townson, Vicar of Headington. ↑

- Letter from Elizabeth Gibson to Sydney Cockerell, 6 May 1911, Cockerell papers, British Library. ↑

- See for example The Freewoman September 19, 1912, pp.358-9; Daily Herald, Sept 24, 1912, p.358; Standard, March 19, 1913. ↑

- This was published as ‘British Women to the Women of Germany and Austria’ in Labour Leader, 24 December 1914, p.5, and as ‘To the Women of Germany and Austria: Open Christmas Letter’ in Jus Suffragii, Jan 1, 1915 p. 28. Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne was the fifteenth name on the list of signatories, who also included Margaret Llwellyn Davies, Isabella Ford, and Sylvia Pankhurst . ↑

- Elizabeth Gibson, 1907, A Book of Reverie, John Lane. London, NY; Elizabeth Gibson, 1909, Welling of Waters, E. Gibson, Hexham; Elizabeth Gibson, 1910, Blossoms of Peace, E. Gibson, Hexham. ↑

- T.K. Cheyne, ‘A Poet among the Social Reformers’, Christian Commonwealth, 25 January, 1911, Vol. XXXI, No 1528, p. 297; and anonymous reviews in Literary Guide, January 1, 1912, p.13, and October 1, 1912, p.159. Thanks to Madeleine Goodall for her help bringing the Literary Guide (precursor of the New Humanist) to my attention. ↑

- Stanton Coit (ed.), 1913, Social Worship, West London Ethical Society, printed at Arden Press Letchworth. Published in two volumes: the first was for spoken word, while Vol.2, which included music, had Charles Kennedy Scott as music editor. Elizabeth’s work was used in both volumes (not all of it listed in the unreliable indexes). ↑

- Kropotkin gave a lecture there on Fields Factories and Workshops. Jane Addams, Twenty Years at Hull-House, with Autobiographical Notes, 1912, Macmillan, New York, available at https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/1325/pg1325.html; Paul Avrich, 1988, ‘Kropotkin in America’ in his Anarchist Portraits, Princeton University Press, pp.79-106. ↑

- Charles Richmond Henderson, 1913, Social Programmes in the West, University of Chicago Press, Chicago. He cites ‘The Mother’ in Charles Richmond Henderson, 1914, The Cause and Cure of Crime, A.C. McClurg & Co, Chicago. ↑

- As late as April 1941, an article by Lester Leake Riley in the Chicago-based national Episcopalian paper The Witness specifically mentions Social Worship’s musical setting of ‘The Man on the Cross’: Witness Vol. 25, No. 6, April 17, 1941, p.6.Stanton Coit (ed.), 1913, Social Worship, West London Ethical Society, printed at Arden Press Letchworth. In addition to their involvement with freethought, Stanton Coit, his daughter Margaret, and his wife Adela were all active supporters of women’s suffrage. ↑

- Maurice Browne, 1955, Too Late to Lament, Gollancz, London. Geraldine P. Dilla, 1922, ‘The Development of Wilfrid Wilson Gibson’s Poetic Art’, The Sewanee Review, Vol. 30, No. 1 (Jan., 1922), pp. 39-56. ↑

- Little Review, April 1916, p.13. ↑

- Dilla, op cit.; Jane Addams to Harriet Monroe, December 26, 1916, [nb misdated in online catalogue]; Jane Addams to Stephen Samuel Wise, December 26, 1916, Jane Addams Digital Edition, accessed August 28, 2023.↑

1 thought on “‘A Poet among the Social Reformers’, Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne: Suffragist, Socialist and Freethinker”

Comments are closed.