This small selection of poems by Elizabeth Gibson (later Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne) is taken from her 1910 collection, From the Wilderness. That self-published book, with its plainer style and more overtly political themes, marks a shift in form and content from most of her previous poetry. My selection gives an insight into her personal stance on feminism, socialism, and freethought in the politically turbulent years preceding the First World War.

For a wider selection of poems, see here.

For more about Elizabeth Gibson, see here.

Download: From the Wilderness selection for download as a docx file

From the Wilderness selection for download as a PDF.

Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne’s poems are out of copyright. This particular selection with accompanying material is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Bibliographic information and notes →

From the Wilderness: a selection of poems by Elizabeth Gibson

Respectability

I went into a meeting in the Town Hall and the speaker was saying:

‘I am a lover of forms and ceremonies;

I would rather that the form were correct, and that the ceremony were imposing, than that the occasion were a sincere one.

I am the greatest liar in the world.

I cause the betraying of women, and the disowning of families.

I cause the churches to be filled with hypocrites,

And the adultress and her husband and her lover to kneel side by side at the high altar to eat the communion bread together.

I cause a woman to live in one man’s house, bearing meanwhile another man’s children.

I make the virtuous censorious; and the easy-going, outcasts.

I help the weakling to become the secret slave of drink or of morphia.

I subdue the strength of the strong, by diverting it into a hundred petty channels.

I lie as a barrier between lover and lover.

I dry up with dust all unoriginal minds.

I ignore dirt, disease, rags, and poverty in general.

I am ashamed of hunger, thirst and desire.

I am mortally ashamed of the body and of all its usages.

I blush to be unclad, either in company or alone.

I spend my last coin on maintaining appearances.

I cannot distinguish between impropriety and immorality,

Or between crime and vice.

And I make sure of every one, who despises me, losing his reputation.’

Then I smiled to myself, and said: “Well lost!” and I got up and left the hall.

Riches

I saw a man driving homeward in a great car

Not drawn by horses; for they would have spurned his roadway,

Which was paved with babies’ bodies.

And his perverted and contemptuous wife was seated beside him.

They alighted, and entered his slave-built palace, and sat down to table.

His bread was made of dead men’s bones ground and cunningly flavoured;

His wine was made of women’s tears and blood;

His shoes were made of men’s skin; and his linen was woven of women’s bodies;

And his couch was made of dead children’s hair.

He arose, and walked in his park, and said to a gardener:

‘Be frugal, that you may thrive’—

The gardener having less than the price of his master’s breakfast,

For himself and his love-won wife and his love-born children to live on.

And I considered my time ill-spent in his company, and fared hurriedly homewards.

Law

I found a man looking jealously into my garden:

And I asked him: ‘Who are you? ‘

And he replied:‘I am a sacred and perfect institution;

No man shall meddle with me;

I am eminently respectable;

I cannot abide poverty and squalor,

For they disturb my dignity:

In short—I am a gentleman.

I allow men to steal as much as they like, or as much as they can, if they call themselves bankrupts;

But I imprison the man who takes a morsel of food for himself or for his starving wife and children.

I allow the rich to steal from the poor; but I do not allow the poor to steal from the rich.

I hang the murderer, but not his instigator.

I punish blasphemy; yet I allow the nightly sale of women’s bodies,

Engendering their hopeless disease and agelong agony.

I punish the unmarried woman who kills her baby;

But I do not seek out and punish its father who refuses to own and support it;

I allow women to be underpaid, and to do hard labour in factories when they are approaching motherhood.

I imprison and torture the women who are brave enough to fight for the freedom of womanhood.

I have few dealings with justice and none with mercy.

I enforce a woman to live with her undesirable and unchaste husband, rather than with her desirable and clean lover,

Because I consider marriage a holy establishment.

I allow the young to be worked to death in factories.

I help the rich to house the poor in warrens where they would not stable their animals.

I take the part of the strong against the weak, of the oppressor against the oppressed,

Because I have a precedent for all these methods.’

And I said: ‘I have no regard for tyrants.’

And he answered: ‘I shall send my minions to punish you.’

And I replied: ‘Then my suffering will prepare the way for your overthrow, and the reign of justice.’

Capital

I passed by the open window of a mansion, and heard one within saying:

‘I hear a battering on my door;

But I will not heed it;

For I know that it is a deputy who knocks—

A deputy from unemployment,

Or a deputy from low wages,

Or a deputy from overwork;

And I do not like these fellows;

For they disturb my peace of mind:

They would divide my loaf with me,

Instead of picking up the crumbs;

They cry: “Let us be partners and brothers,

Instead of owners and slaves.”

They are a shiftless, lazy, good-for-nothing set of vagabonds;

And I will make use of as many of them as I need,

And the others may die as soon as they like;

For I have dreamed a dream, that everything is mine, and that none shall gainsay me.’

So I walked round to the men at the door; and I said: “Come, let us approach him through the open window, and bind him hand and foot, and bring him before Labour, to be dealt with at pleasure.”

Man

I saw a man asleep by the roadside:

His children were straying hither and thither in search of their mother,

Or they were trying to wake him that he might get food for them;

But he slumbered heavily,

Heedless of their dangerous pastimes,

Unconscious of their hunger,

Careless of their nakedness;

And when he awoke, at intervals,

He gazed vacantly around,

And muttered angrily:

‘Where is my servant, Woman,

Who labours without wages,

Whose duty is obedience,

Whose law is my will,

Whose pleasure is my service?’

And I said: ‘You have trampled upon Woman;

You have trafficked in her, and betrayed her;

You cheat her of her very right to live.’

Then he sprang up with a curse,

And, seizing a heavy whip, went in search of Woman,

Leaving his children for the beasts to have pity on.

And I saw the grim figure of Retribution pursue him with a still heavier whip.

Woman

I met a woman walking through the world,

And I stopped to bid her good-day.

She was walking with a will;

So I asked her where she was going.

‘Everywhere’ she replied.

I asked her whence she came,

and she answered: ‘From the ends of the earth.’

‘Of what land are you an inhabitant?’

‘Of every land I have heard of.’

‘Of what city are you a citizen?’

‘Of every city I can imagine.’

‘Where are your children?’

‘All over the earth. Every child that is born is mine. I suckle every living baby.’

‘Who is your husband?’

‘Every man is my husband.’

‘Why have you left him?’

‘That he may know the bitterness of life without me.’

‘When will you return to him?’

‘When he has learnt that I am his equal.’

Then she bade me good day; and I watched her ascend the summit of the world to see how man was faring.

And as she turned I heard God cry: ‘Thou hast done well!’

Sex

I paused for a moment to listen to the voice that is never still, and it was saying:

‘I am the everlasting mystery:

I baffle the scientist, and I baffle the philosopher.

I am Nature’s gift to mankind; and I am also mankind’s tribute to Nature.

No one who has not begotten or conceived a child has made the supreme sacrifice to the Universal Mother.

I cry continually to man: “Create!”

And to woman: “Conceive!”

So that until a being has consummated itself in creation or in conception, it is restless, unsatisfied, and incomplete.

I am invisible; and I work all my works secretly

And I am seen only in results.

I enslave all whom I master;

And I serve all who master me.

I am both the ameliorator and the discipliner of all lives.

I am the source of man’s honour and of his dishonour.

I am the source of woman’s faithfulness and of her treachery.

I am the motive of the mother and of the prostitute,

Of the father and of the profligate.

I am both lover and libertine,

Both panderer and punisher,

Both god and demon.

I am the joy of the fertile and the torment of the barren,

The blessing of the mated, and the curse of the unmated.

I am the source of love, and of lust,

Of passion and of perversion.

I insist continually on myself

In the home, and in the cloister,

In the world, and in the priesthood.

I am wholly ruthless.

I destroy all who resist me, by reason of their ceaseless combat with me;

And I destroy all who gratify me, by reason of their gratification.

Nothing can overthrow me, for I am from the beginning:

Before religion was, I was;

Before society was, I existed;

Before mankind was, I created.

I am the excess of man’s strength,

And the bloom upon woman’s beauty.

I give man the universe for a moment, to rob him of it forever.

I am happiness and tragedy.

I am ecstasy and woe.

I drive mankind with a rosebranch to equal mating and happy fostering of their young;

Or with a knotted scourge to denial, eventuating in insanity, or murder, or suicide.

I deny every man’s god;

I defy every society’s system ;

I cry to every being that I have originated

“Mate purposefully, or perish”—

Heedless of the numerical disproportion of male and female,

Heedless of attraction and repulsion,

Heedless of opportunity and restriction.

I soothe my successes;

I mock my failures.

I am the most incontrovertible fact in the universe.

I am the Eternal Paradox.’

Salvation

I hear a voice crying daily to every man:

‘You are your own salvation;

There is nothing before or after this,

Nothing behind or beyond,

Nothing above or below;

And as soon as you realise this,

You will arise and burn in the earth-fire

Your world-won vices

Of pride and hate, of indifference and self-love;

And in developing

For indulgence, renunciation;

For intolerance, humanness;

For judgment, mercy;

For self-aggrandisement, cultivation of others;

You will become the god that you were born to be,

And will have fulfilled yourself.’

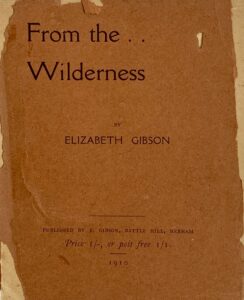

From the Wilderness, by Elizabeth Gibson (later Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne). was published in 1910 by E. Gibson, Battle Hill, Hexham, and printed at the Darien Press, Edinburgh. Price 1/- or post free, 1/1. 52pp. Dedication to M.H. [not as yet identified].

Elizabeth Gibson gave a copy to the Suffragette Library, inscribing it ‘From the Author’; though unsigned, the inscription is in her handwriting. The copy is now in the Museum of London Suffragette Fellowship Collection, accession number 50.82/248.

Judy Greenway’s own copy is inscribed: ‘W. Van Doorn Esq. from Elizabeth Gibson. June 1910.’ Willem Van Doorn was a Dutch educator and critic, who met Elizabeth and her brother Wilfrid Gibson that year, and included work by both of them in the first edition of his anthology Golden Hours with English Poets, published in 1910 in Amsterdam by Meulenhoff.