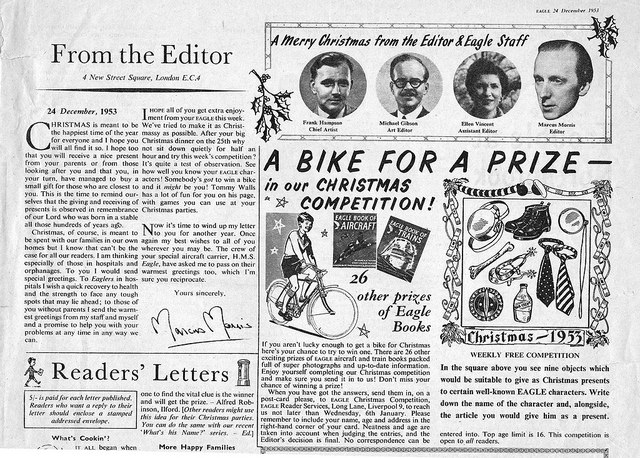

Michael Gibson (1918-2000) author of many adventure books for boys, was art editor of and occasional contributor to Eagle comic from 1951 to 1959. He also contributed occasional drawings and nature notes to its sibling comics, Swift and Robin. From 1954-59 he was also the book editor responsible for the annuals. Sadly, his account of this period remained unfinished at the time of his death in 2000. I have made minor corrections to the text, and added explanatory details in square brackets [ ].

I am in the process of scanning for future upload various pieces of artwork and other ephemera relevant to this chapter. I believe Gibson wrote elsewhere about his time with Eagle, and I would love to hear from anyone with more information. Contact Judy Greenway:

judy[at]judygreenway[dot]org[dot]uk

Obituary of Michael Gibson

Eagle Art Editor

Michael Gibson: First Books and War Work

More about the Gibson Family.

Copyright: This work is copyright and reproduced here with the permission of the Literary Estate of Michael Gibson. Photos and scans by Judy Greenway from Michael Gibson’s collection of books and ephemera. Please contact judy[at]judygreenway[dot]org[dot]uk for further information.

Key Words: art, comic, Eagle, Hulton Press, nineteen-fifties

People: Michael Gibson, Marcus Morris

Working for Eagle

[My nephew] Roland had been a great fan of the newly created children’s paper, Eagle, with its space explorer hero, Dan Dare. He left behind him odd copies and, glancing through these one day I came across the issue celebrating the end of their first year. This contained a lot of information as to how the paper was put together with a care that made it acceptable in schools where the current crop of comics, largely of American origin, were frowned on. It also featured pictures of the staff, headed by the Editor and creator, the Reverend Marcus Morris, describing their various jobs. Though it could in no sense be described as book publishing, the whole set-up sounded most appealing and, at a pinch, could be described as a move in the right direction away from the world [of technical drawing] in which I had so long been trapped. At least it was one better than the joke factory in which I had been briefly involved.

It would be taking a chance if I applied to Eagle for a job but [my wife] Dee and I agreed that I should do so. Maybe this was because in the back of both our minds was the thought that I would be most unlikely to succeed, in that I had absolutely no experience of Fleet Street practices and, in particular, on a weekly paper, which requires a certain sort of temperament. Deadlines must be met no matter what sort of crises may arise, even if it means working all night on occasion to achieve them. And there was, of course, no actual job on offer.

On the plus side, I could claim enthusiasm (rather difficult to prove in a letter of application), an interest in and an ability to write and draw on subjects of interest to children, some experience of the technicalities of publishing such as layout, the use of types in different fonts and sizes, paper sizes and qualities and so on. Finally, my engineering knowledge would be likely to be of some value working on a paper for boys, and that was about it.

I composed a letter to Marcus Morris which, in the circumstances, must have been something of a masterpiece. At any rate Mr. Morris wrote asking me to come and see him. I cannot remember much about the interview, but clearly it went well and I was asked to lunch the following week in a Soho restaurant with Ruari McLean, an old friend of Morris’s, who had been responsible for the general design and styling of the paper and was still employed as a consultant. During lunch it emerged that I had timed my application perfectly, for Charles Green, who had been Art Editor since the beginning, was leaving. They were looking for someone to replace him and, as I was asked to see one more person the following week, John Pearson, the Managing Director of Hulton Press, no less, the company that owned Eagle, it looked as if I was in with a chance. I was, and in due course a letter arrived from Marcus Morris offering me the job, and at a salary quite substantially larger than I was getting as a technical artist. We had been prepared for a drop but it reflected, I suppose, the larger executive role I would now be playing

The children’s papers of my generation between the wars were models of innocence compared to those of today. At the youngest age range were brightly coloured ones such as Rainbow ([my sister] Audrey’s favourite), and Tiger Tim’s Weekly (my favourite), in which the same characters had some mild little adventure in each issue and were uniformly endearing. At a much cruder level but appealing to a considerably wider age range, came picture strips like Film Fun, from the Dundee firm of D.C. Thompson, which featured imaginary adventures of real life film comedians of the day, such as Laurel and Hardy and Harry Langdon. Drawn with great vigour, they were full of action, though nothing more violent than one character accidentally bashing another on the head with a plank to the accompaniment of such expletives as POW! or WHAM! or KERSPLOSH! if someone emptied a bucket of water over someone else. Life for the characters was full of unseen perils, but all really very harmless.

Moving up the age range to the point where reading ability was needed for the first time, came some papers (Modem Boy and The Scout) that combined adventure stories and informative articles. For articles only one went to the no doubt worthy but extremely dull Children’s Newspaper. For stories only, and better written than most, there was Chums, Boys’ Own Weekly and that immortal pair, Gem and Magnet, featuring life in boarding schools in which such things as rebellions could take place without very dire consequences for the pupils, and in one of which Billy Bunter was to take and hold centre stage. Very much downmarket, as one would expect from publisher D.C. Thompson, were Lion, Wizard, Hotspur and others in which athletes, conventional schoolboys and all sorts of other people would suddenly be given superhuman powers, so that they could win through when all seemed lost.

With the war came paper rationing and all these vanished almost overnight. In any case, many of those who worked on them were serving in the forces so that great band of specialist artists and authors which had been their inspiration was disbanded, never to reassemble. Their work may not have been great literature or great art, but it kept literally thousands of children happy and must have encouraged not a few of them to go one stage further to something more serious.

As the war came to an end, shipping space could be spared for non-essential goods and one result was a flood of ‘comics’, as American children’s papers were called, from across the Atlantic. It would take time for British publishers to build up their own teams of artists and writers to produce a home-grown product, so these American comics appeared to be the answer for the time being. Unfortunately most of what came over contained a very high proportion of the very worst of what was being produced across the Atlantic. The strip stories were crudely drawn and full of quite gratuitous violence and general unpleasantness which, of course, the children who read them did not mind a bit, but which filled caring parents over here with alarm. Some schools banned them, but they were not illegal so nothing could be done about stopping their sale. Who can blame the newsagents from stocking such popular and lucrative lines?

One person, however, did decide to do something about the situation. This was the Reverend Marcus Morris, rector of a parish in Southport in Lancashire, who decided that as protest, however widespread, had been unavailing, the only way to fight the menace was to out-perform it and show it up for what it was, a money-making exercise, pure and simple. He already had some editorial experience and he had founded and ran his Parish Magazine Anvil with such flair and imagination that it attracted contributors of considerable standing nationally, and was beginning to be noticed in literary circles. So why could he not, his reasoning went, produce a children’s paper using the format of the American comics, but with the very best of artists and writers, with an editorial policy soundly based on the Christian ethic without this being obtrusive. However, there would be nothing namby-pamby about it. It would be just as robust and full of action as its competitors, a combination of strip cartoons and informative articles, with Dan Dare, Pilot of the Future, adventuring into space as its front cover feature. The back cover strip would tell one of the more exciting Bible stories, beginning with the Apostle, Paul, which turned out to be just as full of action and excitement as features such as Riders of the Range, and PC 49, both based on popular radio shows, or Luck of the Legion, an Eagle original.

The next stage was to find artists with great vigour in their drawing but without the touch of vulgarity on which so many of the other comics seemed to depend. Artists, moreover, who were prepared to work reliably to the tight schedule of a full-page strip in colour per week. They had to understand and master the technique of telling a story in picture form for, although each artist would be given a script of the story line, which would include the words to be contained in each dialogue bubble, keeping the action flowing depended on the artist. He would, for instance, wherever possible, have his characters facing from left to right, particularly at the end of one line and at the beginning of the next. Making a strip cartoon has, in fact, a lot in common with making a film.

To assemble such a team would take time, but first of all Marcus had to find a leader for it, who would join forces with him and supply the technical know-how he lacked, and for this he went to Southport Art School. Luck was with him for there he found and teamed up with artist Frank Hampson in the preparation of a dummy copy of what was to become the children’s paper sensation of the post-war period.

There followed weary months of literally tramping the streets of London in the Fleet Street area, trying to find a national publisher who would take it on. Time and again it was turned down and the Morris bank balance dwindled. He had a wife and two small daughters to support and was by now receiving no income for ecclesiastical duties he was no longer performing, though he had not actually severed his connections with the Church. Then one magical day a telegram arrived from Hulton Press, a medium-sized publishing house, producer of Picture Post, Leader and Lilliput, and a general reputation of being forward-looking and prepared to consider carefully any new ideas that came its way and give them a go. Such an idea was Eagle, and the telegram from them said ‘Hold Everything’! Eagle was in! Once again Hulton Press judgement was proved to be right, though quite how spectacularly right no-one at that stage could possibly have guessed.

Marcus Morris and a skeleton staff were installed in a few rooms (they would later take over the whole floor) of the old Evening Standard building in Shoe Lane. This was a turning directly off Fleet Street, which ran up one side of the black glass Daily Telegraph monolith, with its great open loading bays in which were gantries carrying giant rolls of newsprint fully 8 feet in diameter, ready for when the presses should start rolling. The Evening Standard was half way up Shoe Lane or, for those who prefer to navigate by such things, right opposite The Two Brewers.

Eagle was reached by means of a large antiquated lift with sliding and folding metal doors, which indicated that it had once been the main means of delivering goods to the whole of the back of the building. As I was not there right at the beginning, it would be best for me to describe the layout of the offices and give preliminary thumbnail sketches of those who occupied them and their functions. The first office was a large one, one half of which was taken up, under genial middle-aged Jesse Starke, by people answering readers’ letters, for the postbag swelled with incredible speed. Sometimes the letters needed simple, straightforward, factual answers; sometimes they would be more complex and need considerable research. Others asked for an expansion of something touched on in the text of a strip of other feature. An example of this was in a short, half-page strip we did about the French airman, Louis Blériot’s, first solo flight across the English Channel in 1910. The final frame was a dramatic shot of his crash-landing on the cliffs of Dover, grasping at a rescuer with his left hand. ‘Was Blériot really left-handed?’ our reader wanted to know. In this case I am not sure that we ever found the answer.

Equally difficult must have been this ‘Mekon’ facer. The Mekon was Dan Dare’s great Venusian adversary, a strange-looking being with a vast green head, wearing a t-shirt on his tiny body, who used to float around in space cross-legged on something resembling an old-fashioned flat-iron. How, our reader wanted to know, did the Mekon get the t-shirt off over his head when he wanted to send it to the laundry? Of course there were more serious questions, too, from purely personal problems on religious beliefs to advice on hobbies. All replies had to be vetted by Mrs. Starke (and specialist experts where necessary) to make sure that they were both accurate and did not conflict with any of the beliefs and principles set down by the Editor and small group of advisors. These included educational psychologist James Hemming and the Rev Chad Varah, rector of St. Stephen’s Walbrook, in the City, who was to found and run what would become a world-wide organization, the Samaritans, with its ever-open telephone lines for those in need. Chad was an old Cambridge friend of Marcus, whom he persuaded to write most of the scripts for the stories from the Bible that were a regular feature of the back cover, and in general give his advice on religious matters.

These two advisors, together with the fact that Marcus was himself an ordained clergyman, though of liberal views, made Eagle acceptable and even encouraged by parents in schools from which all other comics were banned.

Sharing the room with the correspondence department were the desks of letterers (at the time of my advent about three of them) whose job it was to transfer by hand (pen and Indian ink) the wording in the speech balloons from the script supplied to the actual balloons appearing on the original artwork, ready for reproduction. Although it was the letterers’ job to copy what they were given, it can be seen from this that script-writer and artist must have complete understanding of each other’s work in order to create the right size of balloon into which the lettering could be fitted.

Next door down the corridor was my office, again a large room in which there was space for part-time Story Editor, Rosemary Garland, to occupy one of three spare desks one or two days a week and for me to be able to see visitors at the same time.

My responsibilities were the design of the text pages of the paper and the general arrangement and illustration (either with photographs or drawings), of any feature that was not one of the main strips. Each issue of Eagle carried one or two short stories apart from the main strips and it was my job to find artists to illustrate them. Part at least of our success was through our policy of being prepared to pay higher rates for work done than anyone else in the field, so that even leading artists used to rates paid by advertisers were quite happy to work for us. Most of these used agents to sell their work so that they did not have to spend time touting round for new clients and then carrying out the business side of the negotiation. A good agent might handle all an artist’s financial affairs, including his income tax returns, but as with so many things in this life, there were good agents and bad ones.

From my point of view as an Art Editor I was in a position to judge very well just how good a particular agent might be, both from my point of view and that of his artist. An important part of the agent’s function would be to make sure that a client’s briefing was properly passed on. In other words that he knew exactly what was wanted in considerable detail. If a character was described in a story as having a dark complexion, he should not be depicted as blond. It was surprising how often an artist would completely ignore what the author had written, and a good agent should pick this up and have the drawing corrected before submitting it.

There were a number of agents on whom I soon learnt I could rely and to whom I went first in consequence. Betty White, Pip Giles and his son, B.L. Kearly, United Artists, and Grestock and Marsh, to name only a few. With some of these, particularly with Jack Marsh of the last-named partnership, I set up a really good working relationship for he would come up with ideas his artists could carry out and not just wait for me to approach him. At the other end of the scale there were one or two agents who would carry some scruffy and sometimes out of date newspaper cuttings of their artist’s work to show to a possible client, in one particular case I know pulling them out of the pocket of a rather grubby macintosh.

If the artist could have seen his agent at work he would have had a fit, but at least there was no dishonesty involved. This could not be said of the experiences of several artists who changed agents on our advice and queried why they were now being paid up to twice what they were getting before. The original agent was, of course, helping himself to far more than the agreed percentage.

It may be wondered why there was not more direct contact between the artists and the editors who were using their work. Why have agents at all? This has already been touched on and from the artist’s point of view an agent spared him the time-consuming business of finding new clients and could provide a good business head in negotiation and other matters at which most artists fail to shine. From the editors’ point of view, telling an artist what was wanted by no means always produced what was asked for at the right time. An agent would keep an eye on this sort of thing, the last point being of especial importance to the editor of a weekly paper like Eagle. The paper must appear, come what may, with all the regular features in their regular spots.

One factor with a paper such as ours was the timing involved if one wanted to appear to be telling a news story more or less as it was happening. All weekly papers are actually printed well ahead of the specified publication date to allow time for distribution so we sometimes had to use some intelligent guesswork, even if one was taking something of a chance in doing so, as in the following case.

A regular feature of Eagle was the centre-spread cut-away drawing, generally by Ashwell Wood, showing the internal workings of something such as a diesel locomotive, a nuclear submarine or even a domestic refrigerator. Anything technically complicated, in other words, and into this category came the speedboat with which racing driver John Cobb hoped to break the world’s speed record on water. A date was set for the attempt. Ashwell Wood prepared a drawing showing the boat at speed, and a short amount of text to go with it celebrating John Cobb’s triumph. All this was timed to appear in the issue of Eagle that would be on the bookstalls the day after the record was captured.

But tragedy struck. With Cobb at the helm carrying out trials less than a week before the record attempt, the boat hit some debris on the lake surface at high speed, overturned in a shower of foam, killing John Cobb instantly.

Distressing as this may have been at a personal level, we on Eagle had to look at this as it affected us, for there was no doubt that we had a major crisis on our hands. The centre-spread for that issue had already been printed with all its trumpet-blowing and congratulations. All the elements of the paper were being assembled ready for the press.

Whose quick decision it was I do not know but, risking the appearance of the paper a day or so late, the centre-spread drawing itself, which by great good fortune could be used unchanged, was whisked back from the presses. The existing copy was re-written as a tribute to Cobb’s past achievements, and over-printed on the drawing in place of the old.

This was an exceptional case, but looking ahead, combined with a certain amount of guesswork, was something we had to take a chance on all the time. This was especially so with our regular sports page on which photographs of athletes who were currently in the news would appear.

The next office along the corridor on the Eagle floor was considerably smaller and was occupied by Ellen Vincent, a lively widow with a small daughter. Ellen’s title was Deputy Editor, which meant that she could make quite important decisions (even of policy) if Marcus was away, but her main responsibility lay in making sure that the scripts, and the strips that would be drawn from them, appeared in time for the printer each week. This was no small task, for basically she was dealing with a number of individuals, each with their own quirks. With one it might be a drink problem, with another it might be domestic difficulties or something else which might give a perfectly valid excuse for the drawing being late.