1869 – 1931

When British poet and aphorist Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne described herself in Who’s Who as a suffragist, socialist and freethinker, she was actively constructing a public identity not just as a writer, but as an activist. But identities can’t be so neatly categorised and controlled. This paper is a slightly expanded version of one given to the Womens’ History Network annual conference, Curating the Female Self, Royal Holloway University of London, September 2024.

Download: ‘I am a Suffragist Socialist and Freethinker’ as a Word docx document

or as a PDF

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Key Words: categorisation, feminism, female identity, freethought, historiography, identity, political identity, politics, relationships, self-framing, Who’s Who, women’s suffrage.

People: Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne, Wilfrid Gibson, T.K. Cheyne

Abstract

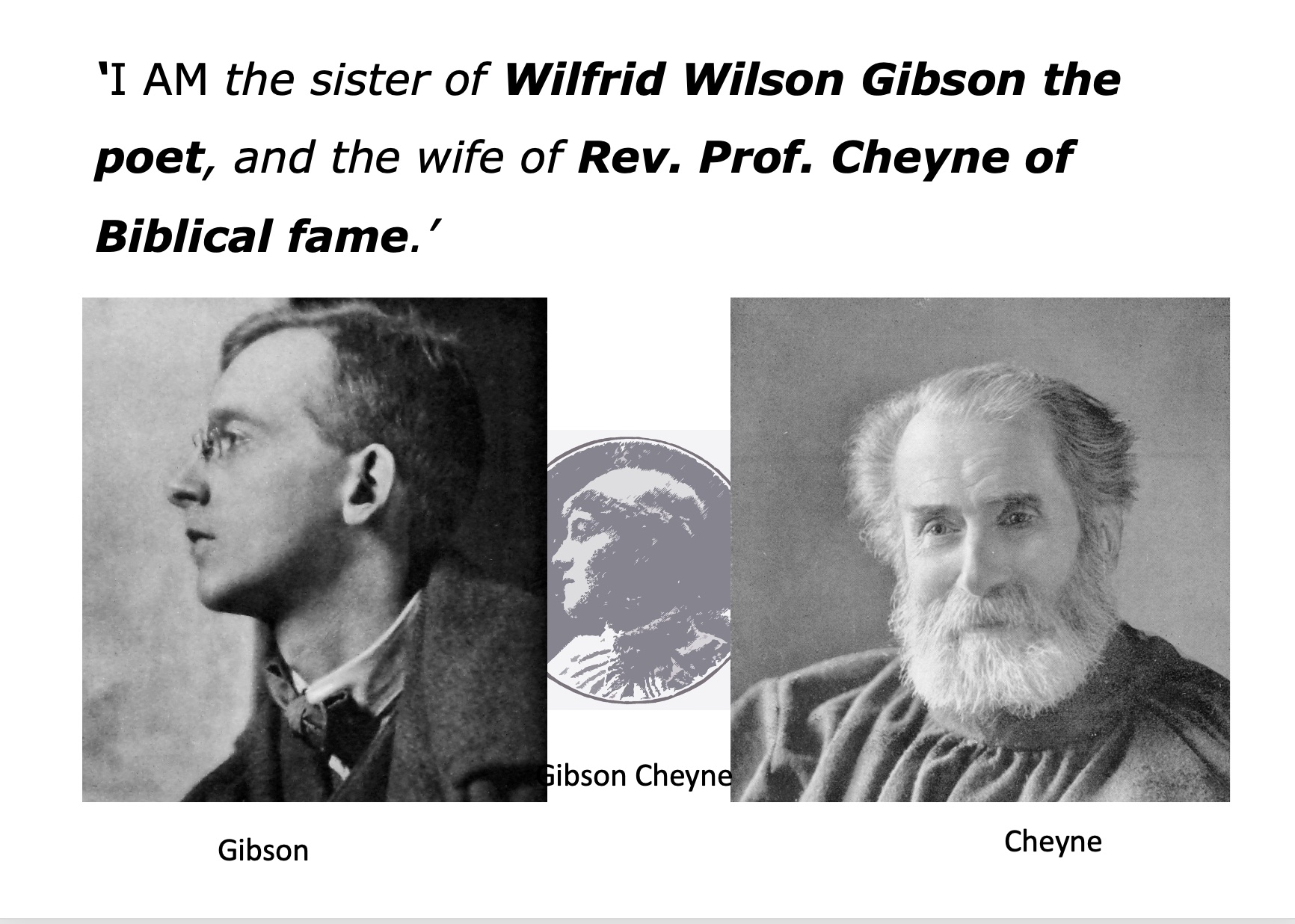

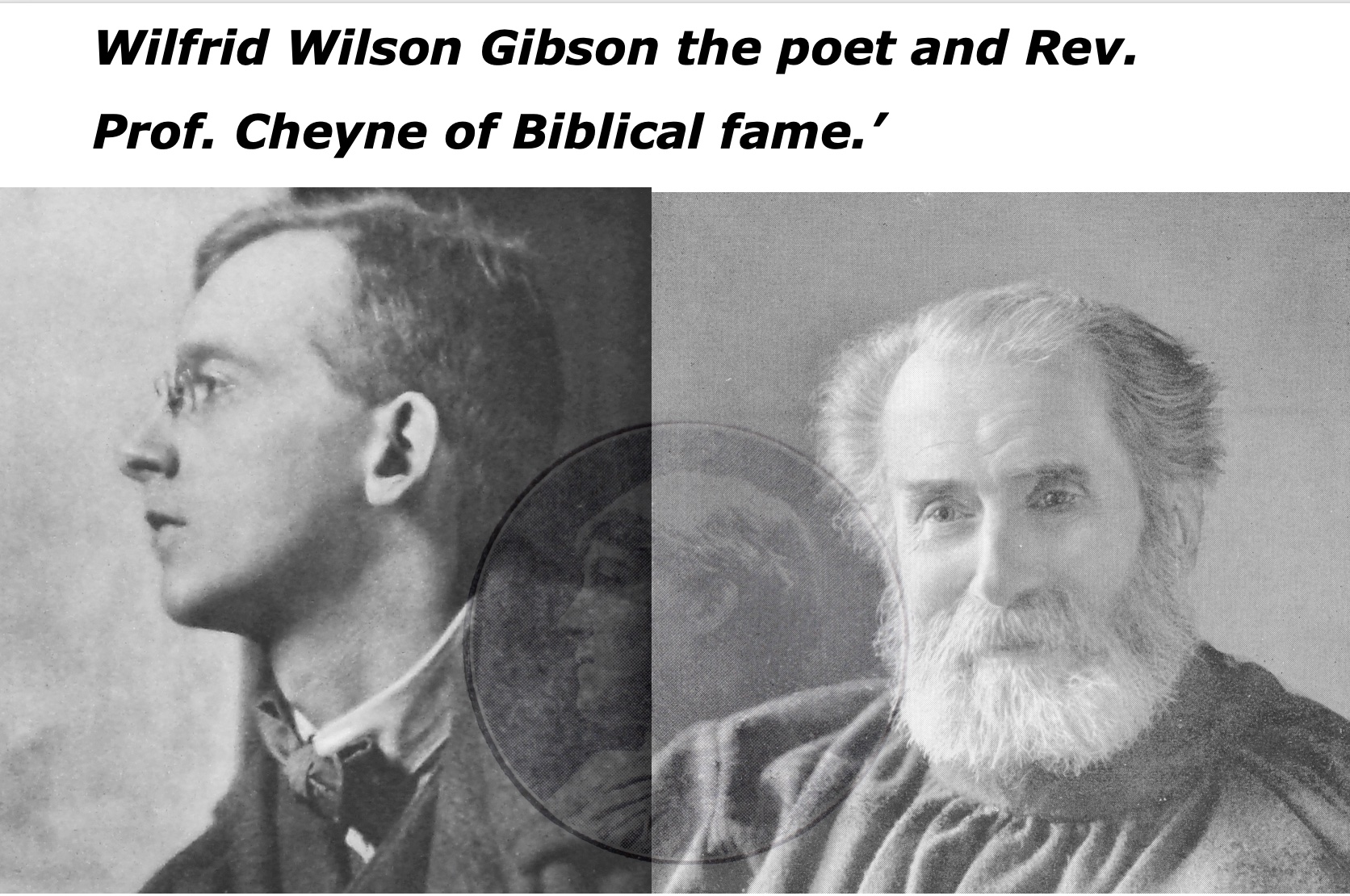

When British poet and aphorist Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne used her entry in Who’s Who to describe herself publicly as a suffragist, socialist and freethinker, she was actively constructing a public identity not just as a writer, but as an activist who situated herself within the radical politics of the early twentieth century. Her public identity was complicated by her familial relationship to men who were, or became, better known than she was: her younger brother, also a poet, and her husband, a controversial Biblical scholar. Frequently referred to as ‘sister of’ one or ‘wife of’ the other, until recently she was remembered, if at all, as a footnote in their lives, her own work diminished or erased.

This short paper discusses some of the shifts and contradictions in Gibson Cheyne’s self-created identity/ies, and how these can be interpreted. It also touches on the often uncomfortable processes of negotiating and re-presenting my own identity: as a person working between disciplines, both inside and outside academia, while researching and shaping my version of someone who was a forgotten member of my own family.

‘I am a Suffragist, Socialist, and Freethinker’:

Shaping a Political Identity in the Early 20th. Century

Judy Greenway

Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne, poet, aphorist and social reformer, grew up in a comfortably off, though not wealthy, family in Hexham, north-east England, where for many years she supported her writing by working mainly as a day governess. She had a close relationship with her younger brother Wilfrid, and nurtured his own development as a poet. Wilfrid’s reputation eventually outstripped hers, and though neither of them is widely — if at all — remembered now, Elizabeth by the end of her life had become almost completely forgotten.

However, in the early years of the twentieth century, she was known both as a poet and for the aphorisms which — unusually for a woman — frequently appeared in such newspaper features as ‘Thoughts for the Day’. Much of her early lyric poetry was inspired by her passionate relationships with both men and women; later on, social and political concerns become increasingly central to her work. In her early forties, she married controversial Biblical scholar Thomas Kelly Cheyne, who shared her progressive beliefs.

At about this time she began to identify herself publicly, in Who’s Who and elsewhere, as a suffragist, socialist and freethinker.[1] What I want to suggest here is that in so doing she was not simply naming beliefs already apparent in her writings, but that, taken in context, those words — the I AM in that sentence — also define and construct a political self. And in so doing they become a political action. (Words can be deeds.)

So — the context: By 1912 Elizabeth was reckoned sufficiently important as a poet to be invited into Who’s Who. In its early years, this reference work had listed only male pillars of the establishment, but by this time it had begun to include noteworthy figures from wider literary and cultural circles, and women were also eligible (though only a few got in). Each entry was autobiographical, and it was up to contributors what to say about themselves. However, apart from politicians, clergymen, and heads of national organisations, it was exceptional for anyone to indicate religious or political affiliations — so much so that Elizabeth’s self-description was joked about in the gossip column of the Daily Mirror.[2]

Had she said: ‘I am a Conservative, Church of England anti-suffragist’, it would hardly have been noteworthy in that august company. But not only did she break the rule of polite society, never to discuss sex, politics, or religion (all of which she already did in her writings): to say ‘I am a suffragist, socialist and freethinker’, in that place, and at a time when suffragette militancy, widespread strikes and social unrest were constantly in the news, was not just unconventional — it was an act of provocation, of defiance — especially for a woman.

These were not the beliefs she grew up with. Her father, a chemist, was active in local politics; at his funeral flags were flown at half-mast on the church, the Unionist Club, and the Territorials — institutions which stood for all that she was so publicly against.[3] As she wrote in one of her aphorisms, ‘He alone is free who is creedless and without nationality.’[4]

But she doesn’t fit neatly into categories — she never did.[5] Her scathing views on bourgeois respectability and sexual morality must have been discomfiting for those feminists and socialists anxious not to have their campaigns tarnished by association with immorality. Though she was on the committee of the Women Writers’ Suffrage League, and an active campaigner against forced feeding of imprisoned militants, women’s suffrage as such was barely mentioned in her work. Her socialism is more evident, though I’ve found no evidence of association with any specific organisation. Her own version of freethought — rejecting all churches and dogmas, while still believing in some sort of God, differentiated her from others calling themselves freethinkers. She never elaborated a theory, nor, as far as I know, ever made a speech — but her poems appeared in mainstream journals as well as the little magazines of literary modernism and the publications of Theosophists, Freemasons, and Ethical Societies. They were quoted by social investigators, set to music, used in new alternatives to traditional religious services, and read out at protest meetings.

I AM a poet, and I AM these other things as well: the identities intertwine. Perhaps those terms ‘socialist, suffragist, and freethinker’ can best be seen not as personal attributes or fixed political categories, but as indications of relationships — created through actions and stitched together by friendships and shared beliefs — within and between the ever-moving and changing social movements of her time.

There are many possible reasons why Elizabeth and her work were so thoroughly forgotten — it is, after all, more unusual for anyone to be remembered, and the ways in which women’s stories in particular get erased are multiple — but I’ve found myself asking whether Elizabeth herself may have played a small, if inadvertent, part in her own overshadowing?

‘I AM the sister of Wilfrid Wilson Gibson the poet, and the wife of Rev. Prof. Cheyne of Biblical fame.’[6]

Wilfrid Gibson’s first appearance in Who’s Who was when Elizabeth mentions him in her 1912 entry. When he got his own entry a year later, he does not mention her. Since he lists only his occupation, address, and publications, this is was probably not a pointed exclusion, but in general he does not seem to have reciprocated her efforts to promote his work.

However, Elizabeth’s brother and husband were the most emotionally significant people in her life, and she was immensely proud of their accomplishments. So it is unsurprising that she often refers to them — particularly in Who’s Who, where mentioning eminent relatives is part of the deal. The quote that heads this section is from an autobiographical note requested by Harriet Monroe, the editor of Poetry magazine. Besides mentioning her brother and husband, Elizabeth lists sixteen of her published books, and again describes herself as a suffragist, socialist and freethinker.[6] But Poetry‘s ensuing published note on contributors described her only as: ‘a relative of Mr. Wilfrid Gibson, the poet, and a frequent contributor to English magazines.’[7] Maybe the magazine’s readers were presumed to be interested only in poetic connections.

A similar thought was perhaps in the mind of the Christian socialist academic Charles Richmond Henderson, whose book cited one of her hard-hitting poems — but described her, not as a poet or a progressive thinker, but only as the ‘wife of the eminent Biblical scholar’.[8] Once, when Elizabeth and her husband both signed a letter to feminist newspaper the Freewoman, it was published under his name alone.[9]

Again, it is commonplace to use connections as a way of introducing oneself, making a bridge to the audience — but Elizabeth also had a tendency to self-deprecation. This is a tendency I have seen in other areas of my research, when women minimise and downplay their own political or artistic work in favour of those — usually men they are close to — whose work they see as more important. Perhaps this lack of self-importance or self-confidence suggests how patriarchal structuring of female identities can become internalised, their marginalisation rationalised. I am not implying that women are responsible for their own erasure, but the processes by which this happens are interwoven — perhaps tangled is a better word — in complex ways.

Ironically, it is primarily because of Elizabeth’s association with her brother, in particular, that it has been possible to retrieve something of her life. Especially in the days before the internet, and digitisation, information about her was often to be found only amongst archival material which had been collected because of him, and his connections — not in her own right.

That is how I discovered her existence: one bored day when working in an American archive, I decided to see if they had anything in their collections about Wilfrid Gibson — who was my grandfather — and they did — and to my astonishment there she was too, a great aunt I’d never heard of. And so here I am now, years later, talking about her, and talking about myself as well.[10]

When I talk or write about her it has often been to audiences who are more interested in her brother or husband, so I am trying to insert her back into — re-member her into — her family, as well as into the social and cultural history of her time.

I AM … her biographer?

This brings me to the often uncomfortable processes of negotiating and re-presenting my own identity: as a person working between disciplines, both inside and outside academia, while researching and shaping my version of someone who was a forgotten member of my own family. I can’t be the only one here today who angsts over my self-description whenever I am asked by a conference organiser or an editor to provide a brief bio.

Speaking for myself, this is partly about a feeling of inadequacy, but it’s also about who gets taken seriously in contexts less welcoming than the Women’s History Network. What you say about yourself has consequences. Saying you are related to your subject may be useful in getting access to sensitive information such as medical records, or family secrets. It can also mean being dismissed or patronised. Being attached to an academic institution may open doors closed to an independent scholar. Interdisciplinary work can mean constantly having to explain and (re)categorise yourself on demand.

Elizabeth once said that we can see no-one clearly through the faulty mirror of their biographer.[11] Of course autobiographers, too, hold unreliable mirrors. Maybe the problem is that neither self nor subject can be fitted neatly into a frame without distortion. Saying ‘I AM’ something is about making a strategic choice. While framing the self, it can only be understood in its specific context of utterance — the creation of a politics of relationship.

[1] ‘See unpublished ms. autobiographical memo from Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne to the Editor of Poetry, [Harriet Monroe], undated but prior to July 1913, Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library: Poetry: A Magazine of Verse. Records, Box 43, Folder 11. Who’s Who, 1912 (which lists her under her maiden name, Elizabeth Gibson) similarly describes her in her own words as ‘a suffragist and socialist and freethinker.’

[2] To take just one contrasting example, her fellow poet and activist Alice Meynell was an anti-imperialist, a vice-president of the Women Writers’ Suffrage League, and a founder of the Catholic Women’s Suffrage Society — but Meynell mentions only her poetry in her own 1912 entry in Who’s Who.

‘This Morning’s Gossip’, Daily Mail, 23 January, 1914, p5.

[3] Newcastle Daily Chronicle, April 26, 1912.

[4] Elizabeth Gibson, 1913, A Book of Reverie, John Lane, London, p.11.

[5] This brief section draws closely on an earlier paper which expands on these ideas in much greater detail: Judy Greenway, 2023, ‘A Poet among the Social Reformers’, Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne: Suffragist, Socialist and Freethinker’ (presentation to the Socialist History Group seminar, Institute for Historical Research, London, February, 2023.)

[6] Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne to the Editor [Harriet Monroe], undated but prior to July 1913, unpublished ms in Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Centre, University of Chicago Library: Poetry: A Magazine of Verse. Records, (Box 43, Folder 11).

[7] Poetry: a Magazine of Verse, Vol ii No 4 July 1913, p.152. The poem was ‘Partings’, which appeared also in Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne, 1913, In the Beloved City He Gave Me Rest, Mrs Cheyne, Oxford, p.34.

[8] Charles Richmond Henderson, 1914, The Cause and Cure of Crime, A.C. McClurg & Co. Chicago. p.39.

[9] T.K. Cheyne [sic], 1912, ‘The inefficacy of Feeding by Force’, letter to the editor in The Freewoman, 2:46. October 1912, p.398. The original letter, signed by both of them is in the Freewoman archives: Subseries 3A: The Freewoman; Dora Marsden Collection, C0283, Manuscripts Division, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library. That they were both involved is made clear in an earlier letter to the editor from Mary Gawthorpe. Freewoman 2:44, September 19, 1912, p. 358.

[10] I discuss the methodological pleasures and problems involved in the early stages of my research in Judy Greenway, 2008, ‘Desire, delight, regret: Discovering Elizabeth Gibson’, Qualitative Research, Vol. 8, No. 3, 317-324. A version of that paper is also available here on my website.

[11] Elizabeth Gibson, 1909, Welling of Waters, E. Gibson, Hexham, p 13.