Anarchists and others debate free love in theory and practice. What is the relationship between social and sexual transformation? First published in Laurence Davis and Ruth Kinna, (eds) 2009, Anarchism and Utopianism. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp.153-170. This version contains a minor update in note 27.

Anarchists and others debate free love in theory and practice. What is the relationship between social and sexual transformation? First published in Laurence Davis and Ruth Kinna, (eds) 2009, Anarchism and Utopianism. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp.153-170. This version contains a minor update in note 27.

Key Words: anarchism, desire, feminism, fin de siècle, free love, love, marriage, performativity, queer theory, sexual politics, speech acts, utopianism

People: Edward Carpenter, Voltairine de Cleyre, Emma Goldman, Edith Lanchester, Lillian Harman, Charlotte Wilson, Karl Pearson, Henry Seymour, Oscar Wilde, Mary Wollstonecraft

Copyright: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.  However, Manchester University Press requires written permission from both them and me if you wish to republish it.

However, Manchester University Press requires written permission from both them and me if you wish to republish it.

Download Speaking Desire as a Word document for personal use.

Speaking Desire: anarchism and free love as utopian performance in fin de siècle Britain

by Judy Greenway

The most beautiful thing around or above

Is Love, true Love:

The beautiful thing can more beautiful be

If its life be free.

Bind the most beautiful thing there is,

And the serpents hiss;

Free from its fetters the beautiful thing,

And the angels sing.

Louisa Bevington, 1895 1

Introduction

Free love, for many anarchists in late nineteenth century Britain, was integral to any vision of a transformed society. A better world was on the agenda, and how to bring it about was the subject of intense anarchist debate. Then as now, anarchism was often characterised negatively as utopian, meaning unrealistic, unachievable. Anarchists often responded by trying to dissociate anarchism from utopianism, insisting that it was not ‘an artificially concocted, fanciful theory of reconstructing the world’, but based on ‘truth and reality’. 2 Tolstoy and Kropotkin, whose ideas inspired several utopian communities in Britain, criticised such experimentation as a diversion from the wider struggle for change. 3

Others, however, saw things differently:

[P]ropaganda cannot be diversified enough if we want to touch all. We want it to pervade and penetrate all the utterances of life, social and political, domestic and artistic, educational and recreational. There should be propaganda by word and action, the platform and the press, the street corner, the workshop and the domestic circle, acts of revolt, and the example of our lives as freemen. 4

This more inclusive approach to anarchist practice, with its emphasis on process, corresponds with the more dynamic and open—ended conceptions of anarchism — and utopianism—explored in this chapter. ‘Utopia’, says Ruth Levitas, ‘is the expression of desire for a better way of being.’ If, as she and others have argued, utopianism is the education of desire, then the propagandising of utopia, the processes of educating desire, may themselves be utopian, transformative, prefiguring a different world. 5And desire, as queer theorist Elspeth Probyn says about sexual desire, is ‘a method of doing things, of getting places.’ 6 For utopian theorists and theorists of utopia, desire in its broad sense is both method and movement. Charlotte Wilson, writing in 1886 about anarchist revolution as a movement away from the darkness of the past and ‘into the darkness of the future … toward the beckoning of a light of hope’, evokes an image of anarchism as exploration, direction and destination: a form of utopian desire. 7

Those anarchists in fin de siècle Britain who spoke out for free love believed that the transformation of intimate relationships was essential to social transformation, neither attainable without the other. They saw its practice as a form of demonstrative politics: a rehearsal or experimentation with new ways to live, an assertion that another world was possible. The main argument of this chapter is that just as the practice of free love can be a form of speech, a text of desire, so, conversely, to speak of free love can itself be the enactment or performance of utopian desire.

The trajectory of the chapter is from free love as a subject of private conviction in the 1880s to free love as an intrinsically public practice by the turn of the century. It begins by examining how a reluctant Charlotte Wilson eventually found a route to publicise her critique of marriage, and argues that she played an unacknowledged part in the process of opening up the discussion of free love. It goes on to show how subsequent anarchist debates on the subject interacted with debates in wider society, framed by the reporting of high profile events which helped shape public attitudes toward the new social movements of the period. Finally, a range of examples illustrates the richness and diversity that increasingly characterised the theory and practice of free love. Its advocates queered the pitch of normality, using rhetorical strategies that denaturalised traditional ideas and institutions of gender and sexuality. Some went further, and turned themselves from sexual spectacle into exemplars of a transformed sexual politics.

‘Free love’ is not a fixed concept but means different things in different contexts, and must be understood by what it is set against. Its advocates oppose it to its dystopian other, unfree love—itself a mutable and historically specific term. In the 1880s and nineties, its opponents represented free love as itself the dystopian other to an idyll of marriage and the family, an idyll teetering precariously on its pedestal as love, sex, marriage, reproduction and the relationship, if any, between them, became topics of increasing public concern.

Principle and reticence in the 1880s: Charlotte Wilson

In the relations between men and women as in all others, I cry for freedom as the first step—and after freedom, knowledge, that each may decide for himself or herself how that freedom can best be used.

Charlotte Wilson, 1885 8

The old cliché that the Victorians never mentioned sex has been replaced by another: that Victorian society was saturated with discussions of it. The interesting questions, though, concern who spoke about it, what they could say, where, and to whom—and, most neglected because hardest to answer, what effect did they have? The struggle to speak out on sexuality, especially for women, was about far more than free speech—it embodied a fundamental challenge to existing gender power relations.

Charlotte Wilson was a central figure in the emergence of English anarchism in the 1880s. At the time, open discussion of free love was rare, despite ongoing feminist campaigns around marriage law reform. Wilson (who refused to rely on her husband’s money) argued for the importance of women’s economic independence, but was reluctant to speak out openly on sexual matters, citing the ‘unclean’, ‘unhealthy’ sensitivity which resulted from women’s ignorance. Contemporary society, she thought, was too ‘morbid’ to deal with such issues. 9 Her reticence meant that her contribution to the free love debate has gone largely unrecognised.

In 1884, Karl Pearson, the socialist statistician, invited Wilson to give a paper at the new Men and Women’s Club, founded for the private discussion of subjects to do with sex ‘from the historical and scientific standpoint’. 10 She declined, and never attended a meeting, but in subsequent letters to Pearson she commented at length on his paper, given at the Club’s first meeting, on ‘The Woman’s Question’.

Motherhood, she argued, should be freely chosen. Many women, like her own mother (and, by implication, herself) were unsuited for it, and in a free society the majority of women might well choose not to have children. In any case, ‘Children apart—it is an intolerable impertinence that Church or State or society in any official form should venture to interfere with lovers. If we were not accustomed to such a thing it would appear unutterably disgusting.’ Friendship between men and women is valuable in itself, and a woman who can select a lover from among her friends is more capable of choosing wisely (only exceptionally, she adds, would free women want more than one lover). 11

When Pearson asked her to present these arguments at the Club, she refused, pleading the mental strain of dealing with ‘matters so trying to overstrung and unhealthy nerves.’ But, she asked, is it even necessary to talk about such things? ‘Have you not noticed that men and women of the New Society which is struggling into being within the old, naturally fall into healthy relations of cordial equality without very much theorising?’ She concludes that she would rather work for political and economic freedom, from which true sexual freedom will follow. 12 Although that was the standard line on sex put forward by many socialists and anarchists, her comments are striking for their emphasis on everyday practice rather than theory as a way to change the relations between men and women; her letters to Pearson repeatedly insist on the interconnection of personal and political issues.

Pearson then gave another paper at the Club, entitled ‘Socialism and Sex’. This seems to have incorporated verbatim passages from Wilson’s letter, and when reproduced as a pamphlet, it included the footnote: ‘Some of the above remarks we owe to a woman friend; they express our own views in truer words than we should have found for ourselves.’ A subsequent edition refers to the letter of ‘a friend’—sex unspecified. Later versions fail to acknowledge Wilson’s contribution at all. 13

One of Pearson’s purposes in setting up the Club had been to gain access to women’s thoughts on sex questions: a kind of raw material for investigation. 14 From that perspective, citing a woman’s letter in his pamphlet draws attention to this scarce source material. But then why obscure it in subsequent editions? Possibly as Pearson became better known he became unwilling to acknowledge women’s contributions to his work. Perhaps this is an instance of the process of the male scientific investigator distancing himself from the female object of enquiry. Whatever the reason, there is no record of Wilson protesting Pearson’s increasingly cavalier appropriation of her words.

Wilson believed at the time that anarchists should publish anonymously, signing herself in print as ‘An English Anarchist’. 15 If she found it too stressful to speak publicly on sexual matters, such anonymity must have made it easier, and in 1885, soon after her exchange with Pearson, she helped to create a forum for debate in The Anarchist, a newspaper edited by Henry Seymour. Kropotkin joined them on the editorial committee, before leaving with Wilson to found the journal Freedom. Rumour has it that at this time Wilson and Kropotkin (who was also married) became lovers. Whether or not this was so, Kropotkin disapproved of public discussion of sexual matters, believing that men and women should work these out between themselves. 16 But under Wilson’s editorship, Freedom, though concentrating on economic and political analysis, did make space for questions of sex and marriage as well.

The first time Wilson addresses these is—remarkably—in her review of ‘Socialism and Sex’ by ‘K. P.’ (i.e. Pearson). In a sort of multiple ventriloquism, Wilson’s review quotes Pearson’s unattributed quotations from her. This way she can discuss and develop her own ideas without explicitly acknowledging them as such. Her critique of marriage is more vehement than before: she refers to the torture, despair, pain and ‘horrible degradation of human dignity’ of ‘the existing hypocritical and unnatural sexual relations’. It is not just state interference that is ‘disgusting’; marriage itself is unnatural and unhealthy, contaminating all relationships between men and women. Expanding her earlier ideas, she urges the need to envision a different future. She rejects Pearson’s proto-eugenicist views on state-regulated motherhood, arguing that social and reproductive freedom for women will transform gender relations: free love is part of a wider conception of a natural, healthy social world. Having, rather unconvincingly, claimed Pearson as an anarchist, Wilson ends by justifying his right (and so, indirectly, her own) to speak about sex, as ‘one who with clean hands and pure heart, dares to scale heights of truth, and to approach every side of life with the reverence of sincerity.’ 17

A year later an attack on marriage appeared in the Westminster Review’s ‘Independent’ section, reserved for controversial pieces. Its author Mona Caird (later a well-known novelist) was a feminist freethinker and radical individualist associated with the Men and Women’s Club. Her article includes arguments and examples taken from Pearson; the final part extrapolates from his (i.e. Wilson’s) views on how the relations between the sexes might be transformed. ‘First of all’, Caird writes, ‘we must set up an ideal, undismayed by what will seem its Utopian impossibility.’ Beginning with an argument for ‘free marriage’ as a private, dissoluble contract, she draws on evolutionary theory to suggest that, guided by science, limitless utopian possibilities lie ahead. ‘It will be found that men and women as they increase in complexity can enter into a numberless variety of relationships … adding to their powers indefinitely and thence to their emotions and experience.’ 18 Although this is sufficiently vague to be capable of different interpretations, it could certainly be taken to imply that the ‘numberless variety of relationships’ includes sexual ones.

Caird’s critique of marriage sparked off a major public debate when the Daily Telegraph relayed it under the headline: ‘Is Marriage a Failure?’ ‘The marriage controversy’, as it became popularly known, was widely taken up in the mainstream press. Thousands of readers responded, filling correspondence columns for months with stories of unhappy and desperate marriages. 19 All this gave Charlotte Wilson another opportunity to return to ‘Pearson’s’ ideas in a front-page Freedom editorial. Encouraged by the widespread dissatisfaction with marriage, Wilson sought to extend the critique: ‘If the kernel [of society] may even be suspected of being unsound, what of the whole nut?’ Although women had benefited from some recent legal and social changes, she argued, most still faced the unsatisfactory alternatives of chattel slavery in the home or wage slavery outside it. Even if laws were changed, conventions defied, economic independence gained, it would not be enough. She concluded:

Women who are awake to a consciousness of their human dignity have everything to gain, because they have nothing to lose, by a Social Revolution. It is possible to conceive a tolerably intelligent man advocating palliative measures and gradual reform; but a woman who is not a Revolutionist is a fool. 20

If marriage was the kernel of existing society, free love was arguably the kernel of a new one. The marriage controversy focused primarily on the wrongs of marriage, rather than the alternatives, but it helped open up wider questions for public debate during the following decade, and Wilson’s ideas played a part in that process.

Sexual anarchy in the 1890s

A teaching which would turn society into groups of harlots.

Lord Egerton, 1898 21

By the 1890s, anarchism, socialism and feminism were on the rise, prompting many anxious commentators to connect sexual and political dangerousness. Sexual anarchy was not just a metaphor: the fears and fascinations that the term evokes can be linked to public perceptions of increasingly visible anarchist activity. Anarchists were responsible for a number of bombings and political assassinations in mainland Europe, and Britain, then something of a centre for international anarchism, was gripped by an ‘anarchist panic’: riots and strikes, bomb outrages and assassination attempts were all attributed to anarchist conspiracies. Scotland Yard set up its Special Branch to deal foremost with the dual menace of Fenianism and anarchism. Before long it seemed that no anarchist gathering was complete without a plain-clothes policeman taking notes and a reporter hoping for scandal; it was at this period that the stereotype of the anarchist with a black cloak and a bomb was propagated. 22

Newspapers, novels, cartoons and learned articles represented anarchist men as mad bombers, deluded intellectuals, or sensation-seeking aesthetes. Women tended to be characterised sexually: de-sexed fanatics like ‘Red Virgin’ Louise Michel; sexualised sirens with disordered morals and disorderly dress; or puzzlingly ‘feminine’ and normal-seeming. Anarchist advocacy of free love was seen as at best an excuse for promiscuity, and the women either seduced into this by unscrupulous men, or themselves no better than prostitutes aiming to degrade all women. 23 Such images may perversely have contributed to the large audiences for anarchist women speakers, and to such episodes as the arrival of prurient sightseers demanding to view the women at Whiteway, an anarchist community in rural Gloucestershire. 24

The repeated association of anarchism with sexual licentiousness meant that anarchists were often forced, however reluctantly, to take a position on the subject. Anarchist women in particular had little choice but to address questions of sexuality: their very identification as women anarchists was already a form of sexual spectacle.

But they were not the only ones seen as a threat to sexual order. A more overt metropolitan subculture of male homosexuality caused alarm, as did the ‘New Woman’ phenomenon, then in its heyday. ‘New Women’ and ‘effeminate men’ were rhetorically linked with social and sexual ‘anarchy’ and actual anarchism. To its enemies, anarchism meant political and social chaos, and sexual freedom in turn would lead to anarchism—the destruction of all order. Anarchists, on the other hand, argued that that chaos, disorder and immorality characterised the system that they aimed to undermine or overthrow, and that anarchism heralded a new order in sexual and social relations.

Sex and marriage were in any case becoming decidedly hot topics. The argument that marriage was often no more than licensed prostitution was commonplace among feminists and marriage reformers, as well as the anarchists who wanted to abolish it altogether. Most socialist and feminist groups, fearing negative publicity that would damage their campaigning, endeavoured to dissociate their critiques of marriage from any suggestion of sexual irregularity. But many anarchists, women especially, saw free love as the basis of a wider struggle around issues of sexuality and gender, central to a critique of an unjust and authoritarian society. For them, it was not a subject for silence. The challenge was to change the terms of the debate.

Many located the discussion firmly within a feminist framework, and saw free love as part of an interconnected struggle around such issues as freedom of sexual expression, sex education, contraception, childcare, and women’s economic and social independence. Although rejection of the state, its laws and institutions, should in theory include rejection of marriage, there was no consensus among anarchists about what this actually involved; the term ‘free love’ was used with a range of meanings, including monogamous but dissoluble partnerships, non-exclusive ‘sexual varietism’ and even—occasionally—passionate but non-sexual relationships.

However, although in theory the call for free love could create a space to speak of same-sex love, most discussion was strongly heteronormative; homosexuality, if mentioned at all, was usually seen as an unfortunate medical condition. The most notable exception to the general silence came from Edward Carpenter, who in 1895 published Homogenic Love in a Free Society, arguing that same-sex love was natural and socially progressive, and should not be persecuted. 25 But shortly afterward, amidst massive publicity, Oscar Wilde was tried and imprisoned for homosexuality; the spectacle intimidated and silenced many writers and publishers.

Freedom, though, ran an editorial attacking Wilde’s persecutors as hypocritical and unjust, and published an article by Carpenter defending same-sex love. This suggested a more inclusive definition of free love, arguing that ‘there can be no truly moral relations between people unless they are free.’ 26 When Carpenter’s friends later urged him to protect himself by claiming to advocate only platonic love between men, he refused: for him, free love must include physical love. 27 He lived openly with his male lover, and argued against silence on sexual matters; in the aftermath of Wilde’s downfall, few gay men in Britain showed such courage.

The Wilde case was only the first of several episodes giving a high profile to ‘sexual anarchy’. Free love hit the headlines again in 1895, after Edith Lanchester, an activist in the Social Democratic Federation, announced to her respectable middle class family that she was entering a free union with James Sullivan, an Irish factory worker. Outraged, her father and brothers had her forcibly incarcerated in a mental asylum. The doctor who committed her cited her socialism, her attachment to a ‘lower class’ man, and her belief in free love—‘social suicide’, he called it—as evidence of insanity, while her father claimed madness had been brought on by over-education. As the more uninhibited of her political comrades paraded outside the asylum, sounding trumpets and singing the Red Flag, influential friends worked behind the scenes, and amidst worldwide publicity—which can only have been boosted by the case’s similarity to the plot of a gothic thriller—Lanchester was released. Many socialists, including some of her SDF colleagues, thought she had brought their cause into disrepute, and a number of former friends now ostracised her. The socialist press, whilst denouncing her incarceration, disapproved of her actions. Freedom, though, praised her assertion of sexual liberty: an ‘anarchistic’ act which would do more ‘for the cause of human freedom … than a hundred years of political action.’ 28

A number of the noisy demonstrators were from the Legitimation League, which campaigned for the rights of illegitimate children. The Lanchester case boosted its activities, providing an opportunity to make free love a more explicit part of its agenda. Mona Caird was an active member, as were many anarchists, and Lillian Harman, an American anarchist feminist who had notoriously served a prison sentence for cohabiting with her lover, accepted an invitation to become Honorary President. When she came to Britain on a lecture tour, and was interviewed in the national press, the resulting publicity led to another surge in League membership. 29

In its journal The Adult, Harman criticised novels such as Thomas Hardy’s Jude the Obscure, and Grant Allen’s The Woman Who Did for their negative depictions of free love. Their unhappy endings, she said, were not true to reality: as her own life demonstrated, it was possible to live happily, without shame and regret, as a free woman and a free mother—the key was frankness. 30 In similar spirit the League encouraged members to make public announcements of free unions and any subsequent children, and a few did so, one pair of ‘marriage resisters’ even putting a notice in The Times. 31 Women, who made up around half the membership and regularly chaired League meetings, often contributed to The Adult praising free love and criticising male writers on the subject for their misogyny.

According to John Sweeney, an undercover policeman who infiltrated the organisation, the authorities feared that this ‘open and unashamed’ attack on marriage laws was the vanguard of an attack on all laws. After the national press published a letter signed by peers and clergymen urging the use of ‘the strong hand of the law’ against the free love movement, the police decided to make a move. 32

They soon found their excuse. In 1898, the Watford University Press, publishers of the Adult, brought out Sexual Inversion, Havelock Ellis’s book about homosexuality. George Bedborough, the paper’s editor, agreed to distribute it. Detective Sweeney bought a copy, and the police pounced. They arrested Bedborough, seizing Ellis’s book and another on free love by Oswald Dawson, the League’s founder, as well as copies of The Adult; all were condemned as obscene at the subsequent trial. The indictment included, as evidence of obscenity, poems and articles by women; the judge was outraged by women’s active involvement with the paper, and tried to bar female spectators from the courtroom. Henry Seymour organised a Free Press Defence Committee that included Edith Lanchester and Edward Carpenter, but much to its annoyance Bedborough did a deal, pleading guilty to avoid jail. Although Seymour, who had taken over editorship of the Adult, repudiated first free love and then anarchism, booksellers would no longer stock it. Soon both the paper and the League folded: to that extent, a success for the police who had, in Sweeney’s words, aimed in one blow to crack down on the publication of material on homosexuality and to kill ‘a growing evil in the shape of a vigorous campaign of free love and anarchism.’ 33

But although such cases had some deterrent effect, especially on the discussion of homosexuality, they also gave mainstream publicity to subversive ideas, and by the end of the 1890s marriage versus free love was a regular, if controversial, topic of debate in novels, plays and stories, newspaper articles and public meetings.

Speaking utopia

A subject … in the vibrations of a first great awakening.

Voltairine de Cleyre, 1897 34

This period saw a general upsurge in utopian writing as well as experiments in living, and free love propaganda increasingly developed more explicitly utopian imagery to parallel its dystopian representation of conventional marriage. Louisa Bevington’s poem ‘The Most Beautiful Thing’ is characteristic of the romantic rhetoric used by many women, emphasising the ‘love’ in ‘free love’.

Such romanticism did not preclude discussion of the obstacles to change. Most anarchists acknowledged the sexual oppression of women under existing social arrangements, and emphasised that change would benefit both sexes. But Charlotte Wilson was not alone in recognising that men and women often had different priorities, and many anarchist women complained, as did other New Women, that New Men were hard to find. 35 In 1896, the individualist Free Review ran an article by Aphra Wilson, called: ‘Wanted: A New Adam’. New woman, she argued, does not want the old Adam: ‘She will not put a foot into Bondwoman’s Lane … She shall take to herself a mate; with her shall lie the choice in childbearing … so shall she be the free mother of strong children.”

She wants ‘dual freedom’ with a New Adam ‘who has not used his sister, Woman; he has not abused her, so he is not her thrall; he is his own man’, who will find freedom through restraint. Together they will travel in love on ‘the Open Road … of perfect freedom—the heroic path of a divine Liberty.’ Aphra Wilson identifies the enemies of this freedom as the Priest, the Licentious Male, and the Man of Science. 36

In earlier years, it had been easier to see science as an essential part of the utopian project, a liberator bearing the light of truth into superstition’s dark corners—and indeed this is how most radical men and many women continued to see it. For instance Henry Seymour, then a fervent free-love propagandist, initially viewed science as something provisional and imperfect that might help free lovers to make a better choice of partners. By 1898, however, he depicted science as essential to any progress towards a new improved kind of human being, and advertised his services as a eugenic matchmaker: free choice was no use without professional guidance. 37

Women tended to be more wary than men of pronouncements about gender and sexuality from scientists who, like Karl Pearson with his increasingly authoritarian eugenicist ideas about the control of women and motherhood, were entering contemporary debates about women’s place with new ideas justifying the same old status quo. During the whole of the period under discussion the sexual double standard, despite constant attack, showed little sign of withering away—indeed it was ingeniously reconstituted in biological and evolutionary terms; Seymour and Pearson were among those arguing that nature, not society, dictated women’s subordinated sexual role.

It was clear to Aphra Wilson and others that women would have to seek liberation on their own terms. Some adapted eugenicist arguments to claim that free love and free motherhood produce healthier and happier children, while others focussed on the psychological benefits of sexual liberation, emphasising not just freedom from the legal and social bondage of marriage, but the positive virtues of choice, and the conditions in which love can flourish. Such women stressed that freedom was about control over their own bodies and desires, an argument which needed to be constantly remade in response to those opponents (and a few proponents) who thought that ‘free women’ meant women’s sexual availability to men.

Charlotte Wilson, writing in the 1880s, had deployed the language of healthy versus morbid sexual and gender relations in a way that took up and reversed dominant medical and anthropological discourses, and this now became a regular tactic in free love debates. (Similarly, in his later writings Edward Carpenter would draw on evolutionary theory to argue that, far from being an index of biological degeneration, homosexuality could represent a higher social development, embodying the best of men and women. This argument was taken up by others, who sometimes referred to Wilde himself as a representative of the higher humanity.) 38

I am not a mere theorist. I have lived that of which I write.

Lillian Harman 39

Although Wilson’s writings reveal her intellectual and emotional engagement with the subject of marriage and free love, it was only in private letters that she referred directly to her own experiences. In the more outspoken climate of the late 1890s that she had helped to bring about, a new generation of anarchist women felt able to be more outspoken about living their politics, drawing on their own lives for propaganda.

At the forefront of this approach were Lillian Harman, Voltairine de Cleyre, and Emma Goldman, anarchist feminists from the USA who each attracted large audiences on their speaking tours of Britain. All three used examples from their own lives to illustrate not just the need for but the possibilities of sex revolution. They confidently asserted the need for a free and natural sexuality which might not be confined to one partner, and shifted the parameters of the debate by discussing the psychology of sexual relationships.

Goldman argued that women must free themselves from internal as well as external tyrants, and brave public opinion to free their true natures as women and as mothers. 40 De Cleyre, herself a working-class mother, had a different take on tyranny, drawing on bitter experience to warn women that living with their lovers would mean becoming at best mere housekeepers, at worst slavish dependants: ‘Men may not mean to be tyrants when they marry, but they frequently grow to be such. It is insufficient to dispense with the priest or the registrar. The spirit of marriage makes for slavery.’

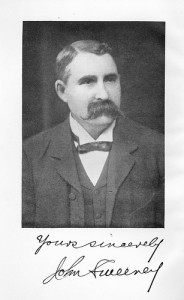

(photo from the Labadie Collection, University of Michigan)

She praised the domestic arrangements of Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin, who lived apart during their marriage, as a model for preserving the spontaneity of love. On her speaking tour of Britain in the winter of 1897-8, de Cleyre spoke to large audiences, who applauded her most radical points on ‘The Woman Question’. In Scotland, one of her most popular topics was ‘The Life and Work of Mary Wollstonecraft’. De Cleyre called for an annual commemoration of Wollstonecraft: ‘Let us have a little bit of she-ro worship to even things up a bit.’ 41

In the 1880s Charlotte Wilson and Karl Pearson had supported a project to republish Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Women, and the Men and Women’s Club was initially called the Mary Wollstonecraft Club; its name was changed because anxious members feared any implication that dangerous ideas might be not only discussed but acted on. Mainstream feminists continued to distance themselves from Wollstonecraft’s life, even while reviving and extolling her writing. But many anarchist feminists of the 1890s extolled her life as a ‘she-ro’ of free love. Biography and autobiography were as important to them as theory in inspiring them to think or rethink their own lives. So Harman and Goldman represented themselves as positive role models for other women; while the sad example of Eleanor Marx, who killed herself after being betrayed by her lover, was taken as evidence of the need for changes that went deeper than legal reform.

Literature served as another prompt for social questioning. Goldman and Harman regularly discussed contemporary works, while in Freedom Charlotte Wilson (now signing herself C.M.W.) analysed Ibsen’s plays in relation to marriage, women, and social prejudice. The paper also carried items about free love in the life and work of Shelley, as well as highly selective extracts from Jude the Obscure and The Woman Who Did, setting out the case for free love—and omitting the unhappy endings. 42 This making and re-making of narratives was taken up with enthusiasm by a younger generation who wanted to live their politics, making their own stories part of the propaganda for a new life.

‘Propaganda cannot be diversified enough if we want to touch all.’ 43 There may have been general agreement about what was wrong with marriage, but there was no single alternative model of free love: instead, there were debates, aspirations, experiments, compromises; failures and successes, adaptation and change. The relationship between principle and practice was never straightforward.

Some anarchists continued to stand against any attempt to propagandise or practise free love—men most often on the grounds that it exploited women, while those few women who publicly opposed it argued that it diverted attention from more pressing issues. Some perhaps had more personally complicated reasons for silence or opposition. Nannie Dryhurst, for example, editor of Freedom’s propaganda column, spoke against free love in a public debate with Lillian Harman. 44 Dryhurst had a long and passionate affair with journalist Henry Nevinson; both were married with children, and despite much agonising, remained with their families. Personal difficulties did not necessarily inspire anarchists to publicly challenge the institution of marriage. 45

Not all free love advocates actually lived in free unions—Henry Seymour, for instance, remained in a lifelong marriage despite his belief that it was practically a gentlemanly duty to provide sexual experience to unpartnered women whenever the opportunity arose.

Although women were more likely than men to favour monogamy—at least serial monogamy—over ‘varietism’ (multiple sexual partners), and love over sexual desire, this was certainly not always the case. While a section of mainstream feminists called for an end to the sexual double standard in the form of chastity for both men and women, most anarchist women still advocated free love as primarily a sexual choice. Hope Clare, for example, writing in the Free Review, used her own experience of unwanted celibacy to urge that women should be free to break the ‘conspiracy of silence’ and speak their desires to men. 46

Some Christian anarchists, following Tolstoy’s teachings, did see the physical expression of sexuality as an unfortunate diversion from spiritual development. 47 Others disagreed, hotly debating what they called ‘the SQ’—the sex question. Tolstoyan Lilian Hunt Ferris wrote about her free union, contrasting the subjugation of women in legal marriage with a truly religious free marriage, which unites love, sex and spirituality. For her, free love meant a natural ‘love without stint’, and fidelity without compulsion. 48 In 1898, several women and men left a collective household set up by the Tolstoyan Brotherhood Church, disagreeing with, amongst other things, its anti-sex (and anti-woman) line. They founded Whiteway, an anarchist community which, with its spirit of tolerance and openness to change, was to see several generations of experiments with free love. 49

It was the ‘out and proud’ approach to free love that made it, in contrast to other unorthodox sexual arrangements, a kind of deliberate propaganda; like marriage, it gave a public face to personal relationships. This often meant social repercussions, even if these were usually less dramatic than Lillian Harman’s imprisonment or Edith Lanchester’s incarceration: jobs and homes could be lost, families estranged, individuals ostracised. Lilian and Tom Ferris devised an unofficial ‘marriage’ ceremony for themselves, and were expelled from the Quakers as a result. 50 Oswald and Gladys Dawson, the individualist founders of the Legitimation League, were repeatedly threatened with eviction because of their highly publicised free union; Gladys was particularly vilified, especially by other women, and once had her face slapped in the street. 51 George and Louie Bedborough married for the sake of their families, while agreeing between themselves to have an open relationship. 52 Having children was an added complication, and some women just took their partner’s name and called themselves ‘Mrs’, for practical reasons. More often, though, women kept their own name even while committing themselves to lifelong partnerships.

Although social stigmatisation affected women in free unions more than their male partners, it may be that for some the loss of respectability (that relative and class-dependent term) was compensated for by the pleasures of transgression and the assertion of a liberated sexuality. However, the public avowal of free love ideals remained problematic for the politically isolated, or those who were involved in mainstream socialist or feminist campaigns where personal unconventionality was seen as a liability. In practice, the most important factor in sustaining a commitment to free love was the creation of an alternative community, such as Whiteway, with shared views on morality and honour and the interdependence of the personal and the political.

If men and women even in such supportive environments did not always achieve the transformed relationships they had envisaged, free love nevertheless remained an ideal worth struggling for and transmitting to a younger generation, who in turn would adapt its meanings according to their own needs and circumstances.

An example of this process of transmission can be seen in the relationship between Rose Witcop and Guy Aldred, who grew up in the years of the New Woman and the utopian revival. In 1907, the young Aldred published a pamphlet arguing that as long as women are economically, legally and socially unfree, all sexual intercourse oppresses them; the answer was revolutionary celibacy. Then he met Witcop, who lived among other anarchists in London’s East End. Both of her older sisters were in free unions, and she plied Aldred with Legitimation League pamphlets on free love, and others, by Lillian Harman’s father, Moses Harman, on birth control. She told him stories about Victoria Woodhull, another notorious American feminist, who once stood for president of the USA on a free love ticket. Aldred was won over, abandoning celibacy; he and Witcop set up home and had a child together. Later, he continued the transmission of free love stories when he described their tempestuous, non-exclusive relationship in his autobiography. 53

Clearly, for most of the individuals I have discussed, free love was crucial to social transformation. By representing marriage as immoral, unhealthy and unnatural, and free love as the moral, healthy and natural basis of a free society, their polemical interventions in the marriage debates reversed the terms of argument and drew attention to, made strange, what was taken for granted. These are classic utopian strategies, seeking to awaken simultaneously dissatisfaction with the existing world and desire for something better.

Such reversals of conventional thought can be immensely exhilarating, and the expression of the joys of free love and the horrors of its opposite gives a sense of what utopia feels like, rather than a plan or narrative of what it might be. To adapt a point from Richard Dyer’s work on musicals, in these speeches and writings ‘utopianism is contained in the feelings’. 54 In the gap between what is and what might be, the desire for change can take root and grow.

But persuasion with words was only part of a demonstrative politics that also relied on the powerful example of lived experience. As Lillian Harman said in an interview with the Daily Mail, ‘My object … was to make it easier for others who might wish to follow in our path, and yet feared the difficulties in the way … What we want is liberty … so that people may arrive by experience at the most desirable form of relationship.’ 55 The experiments in living that flourished at the end of the century rehearsed different possibilities for the future. And the telling and retelling of cautionary and inspirational stories of the relation between theory and practice became part of the education of desire. As sociologist Ken Plummer suggests in Telling Sexual Stories: in order to tell stories there must be a community to listen—and in order for there to be a community to listen there must be stories. 56 Such storytelling is part of the creation and recreation not just of specific utopian communities but of a wider community of utopians.

But telling about free love has significance beyond the stories themselves. Some queer theorists, following the work of Judith Butler, claim that sexual identity is created through performance—put simply, that it is what we do, not what we are. So for example, to say ‘I am a lesbian’ is not to express an inner truth, or to adopt a label, or to play a role: it is to create that self. This theory derives from J.L. Austin’s concept of the performative utterance, in which to say something is to do it. Austin cites as a paradigm case the phrase ‘I do’ in the marriage ceremony: saying the words is the act of assenting to marriage. 57 Perhaps saying ‘I don’t’ to marriage can similarly be a performative utterance—the creation of a dissident, utopian self.

For women and men in the late nineteenth century, to write or speak in public about their own sexual feelings, experiences and desires was still scandalous, as it was to speak publicly as anarchists. The automatic association of women anarchists with sexuality meant that to speak as an anarchist woman was to speak as a sexual woman. Their desire to speak of desire was a propulsion towards utopianism, and—in the desire for free love, free love as the expression of desire, the speaking of desire—such women were in effect performing desire, enacting anarchism, doing utopia.

Judy Greenway

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Lucy Bland, Laurence Davis, Ruth Kinna and Helen Lowe for detailed and helpful comments, and to everyone who encouraged the work while it was in progress, and inspired me to think about it in new ways.

References

Aldred, Guy, The Religion and Economics of Sex Oppression (London: Bakunin Press, 1907)

— No Traitor’s Gait! (Glasgow: Strickland Press, 1958)

Avrich, Paul, An American Anarchist: The Life of Voltairine de Cleyre (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978)

Austin, J. L., ‘Performative utterances’ in Austin, Philosophical Papers (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1961)

Bevington, L. S., Liberty Lyrics (London: Liberty Press, 1895)

Bland, Lucy, Banishing the Beast, English Feminism and Sexual Morality 1885-1914 (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1995)

Butler, Judith, Bodies That Matter: on the discursive limits of ‘sex’ (London: Routledge, 1993)

Carpenter, Edward, Homogenic Love: and its Place in a Free Society (Manchester: Labour Press, 1894, [actually published Jan. 1895])

— The Intermediate Sex: A Study of Some Transitional Types of Men and Women (London: Sonnenschein, 1908)

— Love’s Coming of Age (S. Clarke, Manchester, 1906 edn)

Dawson, Oswald, The Bar Sinister and Licit Love (London: Legitimation League, 1895)

— Personal Rights and Sexual Wrongs (London: Legitimation League, 1897)

Dyer, Richard, ‘Entertainment and Utopia’, in Rick Altman (ed), Genre: The Musical (London: RKP/BFI, 1981)

Ferris, Lilian Hunt, ‘True life and free love’, in A.G. Higgins, A History of the Brotherhood Church,(Stapleton: Brotherhood Church, 1982)

Goldman, Emma, ‘The tragedy of women’s emancipation’, and ‘Marriage and love’, in Alix Kates Shulman, (ed), Red Emma Speaks: Selected Writings and Speeches by Emma Goldman (New York: Vintage, 1972)

Hardy, Dennis, Alternative Communities in Nineteenth Century England (London: Longman,1979)

Lanchester, Elsa, Elsa Lanchester Herself (London: Michael Joseph, London, 1983)

Lees, Edith, The New Horizon in Love and Life (London: A. and C. Black, 1921)

Levitas, Ruth, The Concept of Utopia, (Hemel Hempstead: Philip Allan, 1990)

London Anarchist Communist Alliance, An Anarchist Manifesto (London: 1895)

Oliver, Hermia, The International Anarchist Movement in Late Victorian London, (Beckenham, Croom Helm, 1983)

Pearson, Karl, The Ethic of Freethought (London, Adam and Charles Black, 2nd edn, 1901)

— ‘Socialism and sex’, in Pearson, The Ethic of Freethought: A Selection of Essays and Lectures, (London: T. Fisher Unwin, London, 1888)

— Socialism and Sex (London: W. Reeves, 1887)

Plummer, Ken, Telling Sexual Stories: Power, Change and Social Worlds (London: Routledge, 1995)

Probyn, Elspeth, ‘Queer belongings: the politics of departure’, in Elisabeth Grosz and Elspeth Probyn (eds), Sexy Bodies: The Strange Carnalities of Feminism (London: Routledge,1995)

Quail, John, The Slow Burning Fuse: the Lost History of the British Anarchists, (London: Paladin, 1978)

Seymour, Henry, The Anarchy of Love or the Science of the Sexes,(London: H. Seymour 1888)

— 1898, The Physiology of Love: a study in stirpiculture (London: L.N.Fowler & Co, 1898)

Shaw, Nellie, Whiteway: a Colony in the Cotswolds (London: C.W. Daniel, 1935)

Sweeney, John, At Scotland Yard (London: Grant Richards, 1904)

Notes:

- L. S. Bevington, Liberty Lyrics (London: Liberty Press, 1895) p.7. ↩

- British Library (hereafter BL), Additional MS 50511 fol.176, Charlotte Wilson to George Bernard Shaw, May 5 1886. ↩

- See Dennis Hardy, Alternative Communities in Nineteenth Century England (London: Longman,1979); Nellie Shaw, Whiteway: A Colony in the Cotswolds (London: C. W. Daniel, 1935). ↩

- London Anarchist Communist Alliance, An Anarchist Manifesto (hereafter LACA, Manifesto) (London: 1895), p.11. ↩

- Ruth Levitas, The Concept of Utopia, (Hemel Hempstead: Philip Allan, 1990), p.8. ↩

- Probyn, Elspeth, ‘Queer belongings: the politics of departure’, in Elisabeth Grosz and Elspeth Probyn (eds), Sexy Bodies: The Strange Carnalities of Feminism (London: Routledge,1995), p.2. ↩

- BL Add. 50511 fo.176, Wilson. ↩

- University College London, Pearson Papers (hereafter UCL P) 900/6-10, Wilson to Karl Pearson, 8 August, 1885. ↩

- UCL P, 900/6-10, 12-20, Wilson to Pearson, 8 August and 8 October 1885. ↩

- Lucy Bland, Banishing the Beast: English Feminism and Sexual Morality 1885-1914 (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1995), p.5. ↩

- UCL P, 900/6-10. ↩

- UCL P, 900/12-20. ↩

- Karl Pearson, Socialism and Sex (London: W. Reeves, 1887), p.14; ‘Socialism and sex’ in Pearson, The Ethic of Freethought A Selection of Essays and Lectures (London: T. Fisher Unwin, London, 1888), p.246. ↩

- Bland, Banishing the Beast. ↩

- BL Add.50510 fols.310-11, Wilson to Shaw, 10 December, 1884. ↩

- See Adult, 2:2, (1898). ↩

- ‘Socialism and Sex’, Freedom, 1:7, (1887). ↩

- Mona Caird, ‘Marriage’, Westminster Review, 130, (August 1888), p.200. ↩

- Bland, Banishing the Beast. ↩

- Freedom, 3:25, (1888). ↩

- John Sweeney, At Scotland Yard (London: Grant Richards, 1904), p.181. ↩

- Hermia Oliver, The International Anarchist Movement in Late Victorian London, (Beckenham, Croom Helm, 1983); John Quail, The Slow Burning Fuse: the lost history of the British anarchists, (London: Paladin, 1978); Haia Shpayer, ‘British Anarchism 1881-1914: Reality and Appearance’, (PhD. dissertation, University of London, 1981). ↩

- Shpayer, ibid. ↩

- Shaw, Whiteway. ↩

- Edward Carpenter, Homogenic Love: and its Place in a Free Society, Manchester: Labour Press, 1894. [actually published Jan. 1895]. ↩

- Freedom, 11:94, (1895); Freedom, 9:95, (1895). (Emphasis in original). ↩

- [Note added to original article. February 2014]. He had to be cautious, though. In her biography of Carpenter, published after this article went to press, Sheila Rowbotham notes that in 1909, following an attack in the British Medical Journal on his book The Intermediate Sex, Carpenter wrote to the BMJ to deny that it advocated same-sex sexual intercourse. The letter was not published. See Sheila Rowbotham, Edward Carpenter: a life of liberty and love, (London: Verso, 2008) pp.284-5. ↩

- Liberty, 3:1, (1896); Dawson, The Bar Sinister and Licit Love; Elsa Lanchester, Elsa Lanchester Herself (London: Michael Joseph, London, 1983); Freedom, 9:99, (1895). ↩

- Sweeney, At Scotland Yard. ↩

- Lillian Harman ‘Cast Off the Shell’, Adult, 1:6, (1898); Harman, ‘Eve and Her Eden’, Adult, 2:2, (March 1898). ↩

- Adult 1:6, (1898); Oswald Dawson, Personal Rights and Sexual Wrongs (London: Legitimation League, 1897). ↩

- Sweeney, At Scotland Yard, p.181. ↩

- ibid, p.186 ; Adult, 2:7, (1898) and 2:9, (1898); University Magazine and Free Review, 10:6, (1898). ↩

- Freedom 11:121, (1897). ↩

- e.g. Lillian Harman, ‘The New Martyrdom’, Adult, 6:1, (1898). ↩

- Free Review, 5:4 (1896) pp.377, 386. ↩

- Henry Seymour, The Anarchy of Love or the Science of the Sexes (London: H. Seymour 1888); Seymour, The Physiology of Love: a study in stirpiculture (London: L. N.Fowler, 1898). ↩

- Edward Carpenter, The Intermediate Sex: A Study of Some Transitional Types of Men and Women (London: Sonnenschein, 1908); Carpenter, Love’s Coming of Age (S. Clarke, Manchester, 1906 edn); Edith Lees, The New Horizon in Love and Life (London: A. and C. Black, 1921). ↩

- Harman, ‘Eve and Her Eden’, Adult 2:2, (1898). ↩

- Emma Goldman, ‘The tragedy of women’s emancipation’, and ‘Marriage and love’, in Alix Kates Shulman, (ed), Red Emma Speaks: Selected Writings and Speeches by Emma Goldman (New York: Vintage, 1972). ↩

- De Cleyre, cited in Adult, 1:6, (1898) pp.143-5; Freedom, 11:21, (1897); Freedom, 11:20, (1897); Paul Avrich, An American Anarchist: The Life of Voltairine de Cleyre (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978), p.158-9. ↩

- Freedom 4:39, (1890); Freedom 3:33, (1889); Freedom 6:70, (1892); Freedom 10:106, (1896); Freedom 13:143 (1899); Freedom 10:110, (1896). ↩

- LACA, Manifesto. ↩

- International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam, Max Nettlau Papers 341, Agnes Davies, letter, August 21, 1898. ↩

- Bodleian Library, MS. Eng. misc. e.610/1-6, Henry Nevinson diaries. ↩

- Hope Clare, ‘Stagnant Virginity’, Free Review 7:3 (1896), p.412. ↩

- Hardy, Alternative Communities in Nineteenth Century England. ↩

- Lilian Hunt Ferris, ‘True Life and Free Love’, in A.G. Higgins, A History of the Brotherhood Church (Stapleton: Brotherhood Church, 1982), pp.14-17. ↩

- Shaw, Whiteway. ↩

- New Order 5:12, 5:14, 5:19, (1899). ↩

- Freedom, 11:120, (1897). ↩

- BL Add.7055 fols.69-74, George Bedborough to Havelock Ellis, 26 April, 1922. ↩

- Guy Aldred, The Religion and Economics of Sex Oppression, (London: Bakunin Press, 1907); Aldred, No Traitor’s Gait!, (Glasgow: Strickland Press, 1958). ↩

- Dyer, ‘Entertainment and Utopia’, in Rick Altman (ed), Genre: The Musical, (London: RKP/BFI, 1981), p.177. ↩

- Lillian Harman, ‘Apostle of Free Love’, Daily Mail, (16 April 1898), p.3. ↩

- Ken Plummer, Telling Sexual Stories: power, change and social worlds (London: Routledge, 1995), p.87 and passim. ↩

- Judith Butler, 1993, Bodies That Matter: on the discursive limits of ‘sex’ (London: Routledge, 1993), p.224; J.L. Austin, ‘Performative utterances’ in Austin, Philosophical Papers (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1961). ↩