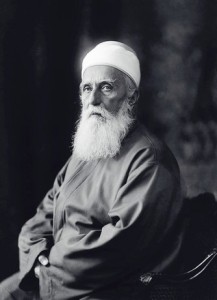

This talk was given at the invitation of the Oxford Bahá’í Community in December 2012, as part of the celebration of the centenary of Abdu’l-Bahá’s visit to Oxford. Abdu’l-Bahá was the son and successor to Bahá’u’lláh, the founder of the Baha’i faith, and was invited to Oxford by Biblical scholar Thomas Kelly Cheyne, husband of the feminist poet Elizabeth Gibson.

Some of the material here has been used and developed in ‘Elizabeth and Wilfrid Gibson: Art for Life’s Sake? Politics Religion and Poetry’ in Dymock Poets & Friends, No. 13, 2014, pp.36-38. More on Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne.

Download: From the Wilderness to the Beloved City: Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne as a Word document. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Key Words: Bahá’í, feminism, Elizabeth Gibson, love, marriage, Oxford, poetry, politics, religion, women’s suffrage

People: Abd’ul-Bahá, Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne, Thomas Kelly Cheyne, Basil Wilberforce

From the Wilderness to the Beloved City: Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne

I’m very grateful for this opportunity to be here on this special occasion to share some of my research into the poet Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne. Elizabeth was my great aunt, but family history apart, I believe that her life and writings give an interesting insight into the great ferment of ideas in the early twentieth century: the debates about gender and sexuality, class and race; the challenges to conventional ideas about morality and religion; the hopes for a new world. All this helped to create supportive conditions for the beginnings of the Bahá’í movement in England. 1

Abdu’l-Bahá was originally invited to Oxford by Biblical scholar Thomas Kelly Cheyne, Elizabeth’s husband, and began his visit by calling at the Cheyne’s home in Parks Road. 2 Abdu’l-Bahá referred to Elizabeth subsequently as ‘a perfect woman’, ‘[an] angel’ — ‘an example to all in her unselfish love’ and care for her husband. 3 (Thomas was partially paralysed, unable to walk, and had difficulty speaking.) In a subsequent letter to Thomas, Abdu’l-Bahá wrote: ‘Your respected wife … is perfect, wise and a truth worshipper … a partner with you in heavenly qualities’. 4 Thomas himself compared Elizabeth to Dante’s Lucia: the saint of rescue, light, and vision. 5

It is unlikely that Elizabeth would have recognised herself in such descriptions. She had a difficult life, and there is some evidence others found her a difficult person. (Though of course the same could be said of many who are called saints…) In one of her poems she says she grew up ‘[B]ristling, wild … devoid of graces’; and though she found a measure of self-acceptance in later life, she often felt an outsider and a misfit. 6 She spoke lightly of this in a verse she wrote soon after moving to Oxford:

I am a stranger to the town;

I am a stranger to the gown;

A foreigner, in speech and dress,

Outlandish, from the wilderness. 7

Nevertheless, it was in Oxford, which she called ‘the beloved city that gave me rest’, that she found the love, acceptance, and happiness she longed for, in her marriage with Thomas. 8 Sadly, it lasted only four years before he died in 1915, aged 73.

I will sketch out her earlier life first, then tell you about the religious and political beliefs that first drew her and Thomas together — beliefs that also drew them to the Bahá’í faith. I will conclude by talking about some of the ideas about God and love to be found in her poetry. 9

* * *

At the time of her marriage, Elizabeth Gibson was in her early forties. Before that she lived with her parental family in Hexham, Northumberland, where she struggled to combine writing with earning a living. Though virtually unknown today, during her lifetime her writing appeared in a range of places, from mainstream journals to the little magazines of literary modernism, from the radical press to publications by Theosophists, Freemasons, and Ethical Societies. Her poems were read out at protest meetings, quoted by social investigators, and used in alternatives to traditional religious services. She also published numerous books of poetry and prose. However, her work, was very uneven in quality, and from around 1910 was overshadowed by the growing reputation of her younger brother Wilfrid Gibson, also a poet. Wilfrid and Elizabeth were very close, and each in their own way rejected what they saw as the pious religiosity, conformism and hypocrisy of their upbringing. As this suggests, the family was not a happy one, and the dedication to poetry, can be seen – especially for Elizabeth — as both a refuge and as a form of resistance, a way to speak out on thorny topics. 10

Elizabeth’s life was emotionally turbulent. In her younger days she loved both men and women, while hoping for marriage and motherhood. Two major relationships ended badly, and after a period of near-suicidal despair she decided that her poems would be her children, her way to connect with the world. (They were also her way to connect with God, for though she rejected organised religion she remained profoundly religious: her writings bear witness to a lifelong spiritual quest.)

Not long after her recovery from this emotional crisis, she received an unexpected fan letter from a stranger – a widower, the Rev. Prof. Cheyne; her books, he said, were what he had been waiting for all his life. Soon, they were writing daily; within months they had exchanged vows by letter and were calling each other husband and wife. For a time Elizabeth resisted legal marriage, reluctant to usurp the place held in Thomas’s household by his niece Dorothy Daniel, who had been brought up there since babyhood. But Dorothy along with Thomas’s circle of friends, made her welcome, and in 1911 the couple wed. 11

As mentioned, what initially drew them together was the sharing of strong values, particularly their commitment to feminism, universal brotherhood, and an openness to all religions. Elizabeth defined herself as a feminist, a socialist, and a freethinker. 12 This was the heyday of the fight for votes for women; she was on the committee of the Women Writers Suffrage League, and she and Thomas publicly supported suffragette militancy, opposing the forcible feeding of hunger strikers. 13 Her feminism encompassed issues of class as well – for instance she was bitterly critical of middle class ‘ladies’ who thought themselves superior to the working class women they exploited. She was also in the minority of feminists going beyond criticism of inequitable marriage laws to challenge the institution itself. Elizabeth opposed sex without love whether within marriage or outside it, asserting that the only moral relationships were those which — regardless of legal or social status — integrated love, passion, responsibility, and mutual respect. 14 I will talk later in this paper about her ideas on masculinity and femininity in relation to religion.

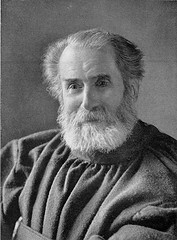

To what extent Thomas was pro-feminist before meeting Elizabeth is uncertain, though there are tantalising hints – for example, in 1879, one of his sermons was privately published by the women’s rights activist and publisher, Emily Faithfull. 15 A later book is dedicated to Frances, his first wife, as ‘the Partner of my toils and Interests’, suggesting their shared intellectual life. 16 His intellectual partnership with Elizabeth was certainly mutual – each in different ways supporting the other’s work.

Alongside feminism, they advocated internationalism, universalism, and anti-racism. Though Elizabeth did not write extensively about race and empire, she denounced the oppression and exploitation intrinsic to imperialism, and the plundering of East by West. She scorned the notion of white superiority: Jesus, she pointed out, would have been dark-skinned. In her poem Kinship she wrote, ‘[M]en are brothers, through and through; [t]heir life-blood flows in one broad stream’. In 1914 both she and Thomas rejected the narrow patriotisms that justified and led to war. 17

Such issues had been a lifelong concern for Thomas: his first published work was a prize essay, written when he was an undergraduate at Oxford’s Worcester College, called The Relations Between Civilized and Uncivilized Races. 18 As its title suggests, this is not an all-out challenge to racial hierarchies, but it does argue against the imposition of cultural values, for respect for indigenous civilisations and religions, and for the benefits of so-called ‘racial mixing’. The essay is an intriguing precursor to some of the themes of his final book, The Reconciliation of Races and Religions, published fifty years later at the onset of the Great War. 19 This gave a central role to Bahá’í, and Thomas hoped the book’s advocacy of respect and interchange between peoples of all religions would further the cause of world peace.

This brings me to the couple’s most strongly shared interest: their approach to God and religion, their spiritual questing. Their beliefs were not identical, and they reached and expressed them in very different ways: Thomas through his career as an eminent pioneer and exponent of biblical criticism, with his scholarly writings; Elizabeth through the emotional journeyings explored in her poetry and prose. Both sought for the truth in all religions, for interconnections rather than differences. It was God that mattered, not churches or dogmas. ‘A creed contains less of God than a hand can hold of the universe, Elizabeth wrote. 20 And: ‘Religion is not God’, /But one of the many ways/ That lead to Him’. 21

In 1913, several of her pieces appeared in a collection providing alternatives to traditional religious prayers, hymns and ceremonies. This is one of them:

‘Who is the Lord, of whom you are the servant?’

‘Gentleness, mercy, holy anger, sincerity, passion, and faithfulness are some of His names.

Others of his names are Gautama of India, Jesus of Nazareth, Emerson of Concord, Abdu’l-Bahá of Persia;

For Righteousness, the Redeemer, adopts many a name of our frail humanity in the course of Its everlasting life; and It is the light of white and dark peoples.

I am the servant of the Lord my God, who is one God, though called by innumerable beautiful names.’ 22

Thomas, while remaining an ordained Anglican, called himself a Bahá’í, and spoke of an interest in joining other religions as well. Elizabeth, though, to my knowledge joined none, though she expressed a preference for ‘the way of Jesus’, which she distinguished from organised Christianity. However, some of her ideas and imagery may have been influenced by Bahá’í prayers and teachings. 23 Many of her writings convey spiritual experiences common to most religions, for example in the poem Night-Joy:

The flaming visions come and go,

Throughout the sacred hours of night;

No tongue can tell, no pen can show

The Beauty of God, as, sea-foam white,

Flame-blue, fire-red, leaf-green, He stands

Unrolling Heaven with His hands,

For mortal hearing, sense and sight.

From the beginning, lo! He spreads

The universe, in wonder wide,

And aeon to aeon welds and weds

In mighty evolution-pride,

The cosmic Force, that sun and space

Creates, yet gives to man the grace

To flow in all Creation’s tide. 24

She never wrote sustained theological argument, instead using poems, parables and aphorisms to express feelings, to challenge the status quo, to provoke. However fragmentary or contradictory, there is what I would call a continuity of concern, a spiritual engagement with the world at all levels, from intimate experience to international politics. When she calls herself a feminist, socialist and freethinker, these become, for her, religious identities. Jesus, she says, was not a Christian; He was a socialist and freethinker. 25 And: ‘God is part of every man …’:

God is not man’s lofty friend,

But man’s beginning and man’s end;

God is man, and man is God –

There is neither slave nor lord. 26

For her, God is woman, too, often referred to as She. Elizabeth writes of the Woman upon the Cross, God our Mother, Parent-God and Mother-Father God. If humans are children of God, sometimes God is the child of Man. As well as challenging the conventional masculinism of religion, this approach expands the notions of human and divine love and responsibility. When I first read Elizabeth’s love poems I took most of them to be about God; it was only later I realised how many of them were addressed to actual human beings. And it was only when working on this paper that I began to think that — for her — this would probably be a false distinction.

In Thomas, she found someone who shared her values, supported her aspirations, and fulfilled one of her deepest needs — to be needed. Before then her strongest feelings had been for Wilfrid, who during her years of painful struggle was, she wrote, not just brother, but sister, father, mother, son and friend to her. 27 That love enabled her in turn to give her deepest love and devotion to her husband. When Thomas died in 1915, Elizabeth was distraught. He had been, she said, ‘a lover to the utmost … [and] he was all to me – parent, child, brother, owing to his utter helplessness’. 28

With the encouragement of Basil Wilberforce, the Archdeacon of Westminster and another early supporter of Bahá’í, Elizabeth tried to overcome her grief by leaving Oxford for wartime London, where she worked with several religious organisations, visiting wounded soldiers back from the Front, while continuing to write. Influenced by Wilberforce’s interest in Spiritualism, (though rejecting the label for herself) she came to believe that Thomas’s spirit survived, and spoke to her. 29 She tried — unsuccessfully as far as I know — to found a new religious order, the Order of the Spirit, setting out its rules as follows:

To Live in and through Spirit.

To live not in time, but in eternity.

To avoid the delusion of appearance, and hold to Reality.

To try, daily, to help souls realise Spirit.

To pray, daily, for the Brothers and Sisters of the Order.

To Pray, daily, for the Dead, as they do for you. 30

But as the War progressed, her religious and political ideas seem to have become more and more conventional, and she ended up waving the flag for church and country. 31 Her mental health eventually gave way, and her final years were spent in an asylum. She is buried, together with Thomas and his first wife, in Holywell cemetery. The shared memorial on the grave says ‘The Truth shall make you free’. Many years before, in a poem called At Holywell, she wrote that those sleeping there ‘had found …[t]heir loving Father and Mother’. 32

Her tortuous emotional and spiritual journey led to this vision of God’s love: familial, multi-relational, masculine and feminine, divine and human; and an interwoven vision of human love: familal, multi-relational, feminine and masculine, human and divine.

In 1913, Thomas Cheyne wrote to ‘My Beloved Friend and Guide’ Abdu’l-Bahá : ‘Love is the secret of the universe, and in love I aspire to live’. 33

So I will end with these lines from a poem Elizabeth wrote to Thomas after his death.

You are mine for evermore:

I did not lose you;

Day after following day,

Still, still I choose you

From all the great, wide world

Of hearing and seeing

As the most dear, and kind

And radiant being.

…

I am yours for evermore;

Than yours, no taming

Of my wild wing: than yours,

No call, no claiming.

Its last words are:

Love has no end, no end.

Love cannot perish. 34

Acknowledgements

Thanks to all the many people who have helped me with my research for this paper, especially Stephen Lamden, Sholeh Quinn and Mina Fazel for their generous encouragement and help with sources and contacts. The richest and most easily accessible resource on the life and writings of Thomas Kelly Cheyne is Stephen Lamden’s website.

Notes:

- See Abdo, Lil, ‘The Bahá ’i Faith and Wicca — a comparison of relevance in two emerging religions’, presented at the 2008 CSNER International Conference, London. ↩

- For the sake of clarity, I will refer to both Cheynes by their first names. ↩

- Blomfield, Sara Louise, 1940, The Chosen Highway, Bahá ‘i Publishing Trust, London, p.168-9. ↩

- Abdu’l-Bahá ‘ to Thomas Cheyne, 31 January, 1914, translated by Stephen Lamden. ↩

- Dedication in Cheyne, T.K. 1914, Fresh Voyages on Unfrequented Waters, London: Adam & Charles Black. ↩

- Cheyne, Elizabeth Gibson, 1914, ‘Life Frustrates Fate’, in The Return Home, p.27, Oxford: Mrs. Cheyne. ↩

-

Cheyne, Elizabeth Gibson ‘A Stranger’, 1914, Oxford, p.11. Oxford: Mrs. Cheyne. ↩

- Cheyne, Elizabeth Gibson, 1913, In the Beloved City He Gave Me Rest. Oxford: Mrs. Cheyne. ↩

- Since I gave this talk, I have expanded and included some of the material covering Elizabeth’s religious and political religious beliefs in Greenway, Judy, 2014, ‘Elizabeth and Wilfrid Gibson: Art for Life’s Sake? Politics Religion and Poetry’ in Dymock Poets and Friends, No.13, pp.36-48. To keep in touch with future research and updates on this topic, subscribe. ↩

- Greenway, Judy, 2004, Shoulder to Shoulder: Wilfrid and Elizabeth Gibson. ↩

- Elizabeth discusses her relationship with Cheyne in letters to her friend Sidney Cockerell between May 6, 1911 and January 4, 1917, British Library Manuscript Collection. ↩

- Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne, unpublished MS autobiographical note [C.1912-13] in the Harriet Monroe collection, University of Chicago. ↩

- See for example, the quote from the Cheynes in the Freewoman, Vol.2 No.44, September 19, 1912, p.358. ↩

- See Greenway, Judy, 2008, Desire, Delight, Regret: discovering Elizabeth Gibson. ↩

- Cheyne, T.K., 1879 The Christian point of view in the study of the Bible : a sermon preached in Balliol College Chapel on Trinity Sunday, June 8, 1879. London: E. Faithfull & Co. ↩

- Dedication in Cheyne, T.K., 1899, The Christian Use of the Psalms, with Essays on the Proper Psalms in the Anglican Prayer Book. London: Isbister & Co. ↩

- Cheyne, Elizabeth Gibson, 1914, ‘Kinship’, Oxford, p.40. See also ‘The Coloured’, 1911, in Way of the Lord, p.44. Oxford: Mrs. Cheyne. ↩

- Cheyne, T. K., 1864, The Relations Between Civilized and Uncivilized Races. A prize essay read in the Theatre, Oxford, June 8, 1864. Oxford: T&G. Shrimpton. ↩

- Cheyne, T.K., 1914, The Reconciliation of Races and Religions. London: A.&C. Black. ↩

- Gibson, Elizabeth, 1908, in Foam of the Wave, p.16. Hexham: Elizabeth Gibson. ↩

- , Gibson, Elizabeth, 1908, ‘God and Man’, in A Pilgrim’s Staff, p.60. Cranleigh,Surrey: Samurai Press. ↩

- Cheyne, Elizabeth Gibson, 1913, in Stanton Coit (ed.) Social Worship, Vol.1, p.14. London: West London Ethical Society. ↩

- Stephen Lamden first suggested to me that some of Elizabeth’s poems and prayers reflect Bahá i’i influence. (See note 28 below). I would love to hear of any other parallels or echoes that may be spotted by readers. ↩

-

Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne, Resurrection, 1915, Mrs. Gibson Cheyne, London, p.91. ↩

- See Cheyne, Elizabeth Gibson [1914?] ‘Jesus and Christianity’ p 23, in The Son of Man is Come. Oxford: Mrs. Cheyne. ↩

-

Cheyne, Elizabeth Gibson, 1914, ‘God in Man’ Oxford, p.12. Oxford: Mrs. Cheyne. ↩

- See ‘Of a Brother’s Love’, ibid p.37. ↩

- Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne to Sidney Cockerell, 27 February 1915, British Library Manuscript Collection ↩

- Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne to Sidney Cockerell, 4 January, 1917. British Library Manuscript Collection. ↩

- Printed card ‘The Order of the Spirit’ (founded August 15, 1915) accompanying MS letter from Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne to Sidney Cockerell, London, August 17, 1915, British Library Manuscript Collection. Stephen Lamden has kindly pointed out to me that the phrase ‘Pray for them as they pray for you’ can be found in a quotation from Abdu’l-Bahá in Abdu’l-Bahá in London, 1912, p.96. London: Longman Green & Co. ↩

- In her last known publication, 1918. The Wilderness Shall Blossom as the Rose. London: J.W.Sparks. ↩

- Cheyne, Elizabeth Gibson, 1914, Oxford, p.31. Oxford: Mrs. Cheyne. ↩

- T.K. Cheyne to Abdu’l-Bahá, October 23, 1913. ↩

-

Cheyne, Elizabeth Gibson, 1915, ‘For Ever’ in Resurrection, p.143. London: Mrs. Cheyne. ↩