This article was first published in 2011, as the preface to Anarchism and Sexuality: Ethics, Relationships and Power, eds. Jamie Heckert and Richard Cleminson, Routledge, Abingdon and New York, pp. xiv-xviii.

This article was first published in 2011, as the preface to Anarchism and Sexuality: Ethics, Relationships and Power, eds. Jamie Heckert and Richard Cleminson, Routledge, Abingdon and New York, pp. xiv-xviii.

Download: Sexual Anarchy, Anarchophobia, and Dangerous Desires as a Word document. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Key Words: academia, activism, anarchism, anarchophobia, coming out, danger, desire, fear, freedom, liberation, organization, second wave feminism, sexuality, sexual politics, transformation, women’s liberation movement

Sexual Anarchy, Anarchophobia, and Dangerous Desires

Anarchism and Sexuality: Ethics, Relationships and Power is a timely intervention into current debates on sexual politics. There is a new excitement about anarchism, and about the relationship between anarchism and sexuality: a sense of creativity and potential, as new connections are made and old ones rediscovered. The Anarchism and Sexuality conference which was the initial inspiration for this book is just one example, providing a space where a diverse and passionately engaged group of participants could come together and discuss research, personal experience, and political practice. 1 Meanwhile, sexual anarchy, alias ‘western decadence’, is blamed for everything from natural disasters to 9/11, and misogyny and homophobia are playing a significant part in the resurgence of the political and religious right. Simultaneously, in the latest twist in an old story, war-mongers and political opportunists appropriate the language of feminism and gay rights to assert the superiority of ‘western civilisation’: part of a long history of using claims about the relative status of women, and attitudes towards sexuality, to valorise one group over another. Such ‘us and them’ accounts erase differences and commonalities within and between communities, and obscure past and present struggles for change. If there is one thing that unites fundamentalists and bigots of all persuasions, it is their attachment to the so-called ‘natural order’ of sex and gender hierarchy, and their horror of those who threaten it. In this world view, sexual liberation is a variation on anarchism: an attack on the foundations of society, a form of terrorism: anarchy as chaos.

The interplay between sexual authoritarianism and anarchophobia is nothing new. Coming out as an anarchist has some similarities with coming out as gay, and meets with a similar range of responses, from tolerant amusement, to contempt, to hatred and violence. Like ‘deviant’ sexuality, anarchism may be denounced as an immature phase to be grown out of, as dangerously seductive to the young, and/or as an intrinsically violent threat to the status quo, attitudes that mix together fear, fascination and fantasy in a toxic stew.

But important though it is to address prejudice based on ignorance, the truth is that anarchism and sexual nonconformity do indeed threaten existing power relationships. For this reason, refusing to call oneself an anarchist, or gay, or queer — whether from a theoretical rejection of identity politics, a wish to escape damaging stereotypes, or a desire to transcend labelling — provides only a temporary breathing space. It could be argued that to avoid the labels perpetuates stigmatisation and erasure, that sense of a politics-which-must-not-be-named. Ultimately, whatever words we do or do not use, expressing dangerous desires will meet with resistance from those whose power and authority depends on maintaining the status quo.

The association between sexual and political dangerousness began long before anarchy acquired its ‘ism’. By the late nineteenth century, growing numbers of people in the USA and Europe were speaking out and organising as anarchists. The commentators who responded to the rise of anarchism with dire predictions of social chaos also railed against the sexual anarchy exemplified by the New Women of the period, who dared to speak of sex and gender and question patriarchal power, and by those men who were beginning to formulate new sexual identities and question or refashion masculinity. The challenge for sexual and political dissidents was to reverse the discourse and develop positive identities while critiquing the very notion of ‘civilised’ society. Some anarchists, feminists and sex radicals who met through friendship networks, or encountered one another’s ideas in campaigns around such issues as free speech, marriage law and reproductive rights, began to develop a politics which intertwined their different perspectives.

But not all anarchists, then or since, have seen sex and gender issues as important – another reason why a book such as this is not just welcome, but necessary. Reading it, I was reminded of my own early involvement with anarchist, feminist, and lesbian and gay liberation groups in the nineteen-sixties and seventies. We soon discovered that we were not the first to link sexuality with politics; Emma Goldman and Edward Carpenter were hailed as pioneers, their writings reprinted, their names adopted by a variety of groups and organisations. Those of us in anarchist groups tried to re-invigorate them with some of our new ideas and rediscoveries while confronting their sexism and heterosexism, but with limited success; all too often the response was that of course anarchists are in favour of women’s and sexual liberation, so what’s to discuss? This attitude of ‘Do what you want to do but don’t make a fuss or expect us to talk about it or change our ways’ has a long history in anarchism, and has been repeatedly challenged from a variety of standpoints. Revising what is thought of as ‘anarchist tradition’ is one way of doing this, as is critiquing anarchist practice in the present.

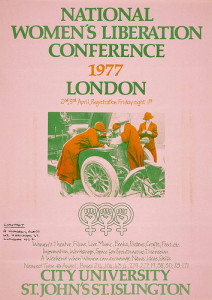

The latter is what I attempted to do in my first ever piece on anarchism and sexuality, in an anarchist newspaper in 1975. In part an excited report of a Women’s Liberation conference on sexuality, the article argued against the glib deployment of a rhetoric of sexual liberation which allowed anarchists and left libertarians to evade the problems and contradictions in their own lives: ‘It is easier to theorise and to talk about what we would like to be than to talk about what we are.’ 2 I wanted to encourage readers to take on board not just new ideas about sexuality, but new ways to discuss it. I recall this long-forgotten piece now, because the excitement of that conference, that electric sensation as personal and political suddenly connected in our own lives, not just as rhetoric or theory, was buzzing around again at the 2006 Anarchism and Sexuality conference — and it is such feelings, recaptured in some of the pieces in this book, which help make change seem possible.

In different times and places, the struggle for sexual and gender liberation takes on different shapes and emphases. In the USA and Western Europe, the anarchists, feminists and sexual radicals of the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century needed to establish ways of discussing sexuality in the face of censorship and social disapproval. In the early nineteen-seventies, when talking publicly about sex was more acceptable, the focus was on the sexism and heterosexism not just of what was then called ‘straight society’, but also of the sixties ‘sexual revolution’ and the radical left. Experimentation with alternative lifestyles played an important part in the sexual politics of both periods. Today, the idea of ‘sexual freedom’ seems to be trapped in a hall of mirrors, reflected in the grotesque shapes produced by a multimillion pound pornography industry and globalised sex trade, and by sex-obsessed religious conservatives predicting Armageddon, but also in the smooth and glossy surfaces of a progressive liberalism which is far more limited and restrictive than it appears to be. The question now is, how to expose the exploitation and oppression that lie behind the mirrors, and to find ways to rethink what sexual freedom could mean.

A recurring theme in all these different contexts has been the need to create spaces in which to explore new ideas and solidarities, practise new ways of relating to one another, and begin the processes of change. In the early days of the seventies Women’s and Gay Liberation Movements, process was all-important. To meet to talk about sexuality meant also to think about the conditions that made such a meeting possible. Meetings, conferences and workshops were organised non-hierarchically, with an emphasis on sharing and listening. The aim was to be inclusive; most events were free or as cheap as possible, with childcare provided by groups such as Men Against Sexism. And the conduct of such meetings, though it did not always live up to our ideals, often felt far more anarchistic (in the positive sense) than anything I had experienced in an anarchist group.

A recurring theme in all these different contexts has been the need to create spaces in which to explore new ideas and solidarities, practise new ways of relating to one another, and begin the processes of change. In the early days of the seventies Women’s and Gay Liberation Movements, process was all-important. To meet to talk about sexuality meant also to think about the conditions that made such a meeting possible. Meetings, conferences and workshops were organised non-hierarchically, with an emphasis on sharing and listening. The aim was to be inclusive; most events were free or as cheap as possible, with childcare provided by groups such as Men Against Sexism. And the conduct of such meetings, though it did not always live up to our ideals, often felt far more anarchistic (in the positive sense) than anything I had experienced in an anarchist group.

Our ideas were inspired by the sharing of personal experiences, but some of these were easier to talk about than others, and often it was a group discussion of a pamphlet or article which made it possible to begin the difficult and exhilarating process of linking theory and practice. In London, we read articles on sexual politics from Italy, Germany and France as well as from the USA and the UK; they were produced and reproduced, translated and retranslated, often hand-typed and duplicated, given away or sold at cost price.

Since then, desktop publishing and the internet have transformed the possibilities of communication. Today, in very different social and political circumstances, the debates continue in new forms, only now some of them are going on inside as well as outside the scholarly academy — a shift of context that has raised new questions about theory, structures, and the relationships between academic and activist work. Insofar as Women’s Studies, Lesbian and Gay Studies, Queer Studies, and now Anarchist Studies, have a toehold in academia, it is because they have been fought for by staff and students who wanted the opportunity to integrate scholarship and political commitment, to challenge the educational status quo, and to contribute to the development of new ways of understanding and changing the world.

These gains have brought new anxieties, quite apart from the struggle to hold onto hard-won courses in times of financial cutbacks and political paranoia. There is the not unjustifiable fear of stigmatisation or at least of not being taken seriously as a scholar. Years ago, one of my students had her thesis proposal for a critique of scientific theories of homosexuality rejected by a homophobic committee, on the grounds that it was intrinsically biased (that is, that she was a lesbian, and not a scientist) and that there was no scholarly basis for such a study. Anarchist scholars have encountered similar institutional prejudice. What helped me to get that decision reversed was being able to cite as a precedent the (then tiny number of) relevant academic publications. 3 The more that such scholarly work is published in these fields, the more it increases the possibilities for others – another reason this book will be so welcome.

Another problem for those who work as academics is how to do research and writing in a way that reaches out to a variety of audiences, and bridges the perceived gaps between theory and activism. This is not just a question of the accessibility of ideas and language, but of where to publish or speak, when only certain publications and venues are academically acceptable. Moreover, many academics feel under pressure to produce theory with a capital T. For those who feel that one advantage of anarchism is that it neither has nor needs a theoretical Big Daddy, the drive towards theory is politically counterproductive, although others have been creatively inspired by it to take old ideas in new directions. Meanwhile, some activists hold theory, history, academic work of all kinds, in contempt, as though ideas can only be credible or effective when seen to emerge from ‘real life struggle’ as they define it. It can feel as though rather than integrating different parts of our lives, we have just multiplied the occasions for feeling defensive and hopelessly compromised.

But we need to sidestep the polarisation of ‘activism’ and ‘academia’, theory and practice. History, theory, reading and writing can all be forms of resistance and activism. A more constructive response is to find ways of bringing together different perspectives, analyses, ways of doing things: not answers, but questions: not a single, smooth, impenetrable surface, but rough edges which can spark off one another, provide new points of access. Standard methods of propagating ideas — meetings, conferences, books and articles — can be subverted in form and content to become spaces where past, present and future are re-imagined and new ways of thinking become possible. A book like this, mingling prose and poetry, theory and autobiography, is just such a space, a gathering place to explore with serious pleasure the interplay between sexual and social transformation.

↩ back to top

Notes:

- Anarchism & Sexuality: ethics, relationships and power, University of Leeds, 4 November 2006. ↩

- Judy Greenway, 1975, Questioning our Desires, Wildcat 6:6, London: Wildcat. ↩

- The most important of these in making the case was Jeffrey Weeks’ pioneering work from 1977, Coming Out: homosexual politics in Britain from the nineteenth century to the present, London: Quartet. ↩